Issue, No.33 (March 2025)

Labor Market Returns under Educational Expansion in the Americas: Is the Value of Educational Credentials Changing?

Over the past 50 years, the expansion of higher education has been predominantly driven by industrialized nations. This growth has been associated with strengthening educational institutions by promoting secondary education completion, aligning with economic cycles, and labor markets that increasingly prioritize formal education. This trend underscores the growing significance of higher education in shaping economic cycles and labor markets (OECD, 2023). In this context, the long-standing debate in sociology and economics has revolved around the question of how educational credentials are valued, given a specific institutional context or labor market, in creating incentives for both jobseekers and employers to invest in education and how they fare in terms of their relative scarcity. It is well established that the economic returns to education depend on several macro-level factors, in which the articulation of states, labor markets, and households portray the different institutional arrangements of welfare regimes (Barrientos, 2009; Fiszbein, 2005).

On the other hand, the Latin American region has witnessed a late expansion in education, encompassing both the primary and secondary levels, due to sectoral policies enacted since the 1990s in various countries (Marteleto et al., 2010). These changes occurred amid transitions to liberal welfare regimes characterized by a generally weak provision of social protection and increasing deregulation in labor markets. The reduction in labor income inequality has been a significant factor in the consistent decline in overall income inequality, which is a key outcome of our research. Enhanced access to compulsory education has played a crucial role in narrowing the income divide between high- and low-skilled occupations (Levy & Shady, 2013; Lustig, Lopez-Calva and Ortiz-Juarez, 2016; Schincariol et al., 2017).

In this context, it is worth wondering what the association between educational attainment and wages would look like across the liberal pool of countries in the Americas. The weaker coordination between the deregulated labor markets and the educational institutions in this context may allow us to observe the variation in trends between educational expansion, returns to education in the labor markets, and the relative value of educational credentials.

It is important to note that the potential benefits of skill-biased technological change may not diminish the differences between educational credentials, thus providing reassurance about the value of education in the labor market. Alternatively, the labor market landscape could shift dramatically if only highly educated individuals benefited from these changes, while workers with lower skill levels faced displacement due to the automation of routine jobs (Autor & Handel, 2013). Nevertheless, the growing number of highly skilled workers (such as university graduates) could also impact the relative standing of workers, similar to the increase in primary and secondary education graduates following educational reforms in Latin American nations (e.g., Brazil, 2001; Chile, 2003; Mexico, 1993; Uruguay, 2009) (Marteleto et al., 2010). These shifts may diminish the value of educational qualifications by altering their relative values. The impact of these trends on labor market returns in liberal regimes throughout North and South America is the primary question addressed in this report.

Data and Methods

We used LIS data to advance the findings of our study1, and explore the main trends in how educational attainment value has changed over the last three decades in the Americas, a region barely studied in the literature. We employed data from 11 American countries (Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Guatemala, Mexico, Panama, Peru, Paraguay, United States, and Uruguay) between 1990 and 2019. From this, we draw a sample of labor market entrants (employees 25-35 years old) comprising a sample of 2.033.710 people, to better approximate the early career job-matching process (Bol, 2015; Di Stasio et al., 2016).

The LIS data include a rich set of income, wage, and education variables. The educational categories were derived from the variable educlev. We coded the original LIS values of this variable into five educational categories according to the UNESCO classification (ISCED) of educational levels (UNESCO 2012). Primary education comprises the ISCED Levels 1 and 2. It includes lower secondary education in virtually all countries, which maps the final cycle of primary education (usually grade 6th to 9th. For example, “middle education” in the US, “premedia” in Panama, “basic cycle of middle education”, in Uruguay, or 7th and 8th grade in Chile. Secondary education includes ISCED Level 3. Tertiary vocational education cluster ISCED 5 programs, including short-cycle tertiary education and between 0.2 and 0.5 percent of post-secondary non-tertiary education (vocational) (ISCED 4). The University/UG degree (300,312) maps ISCED 6, which groups bachelor’s degree (“undergraduate degree”) or equivalent. Finally, postgraduate degrees represent ISCED Levels 7 and 8, including master’s and PhD degrees, respectively.

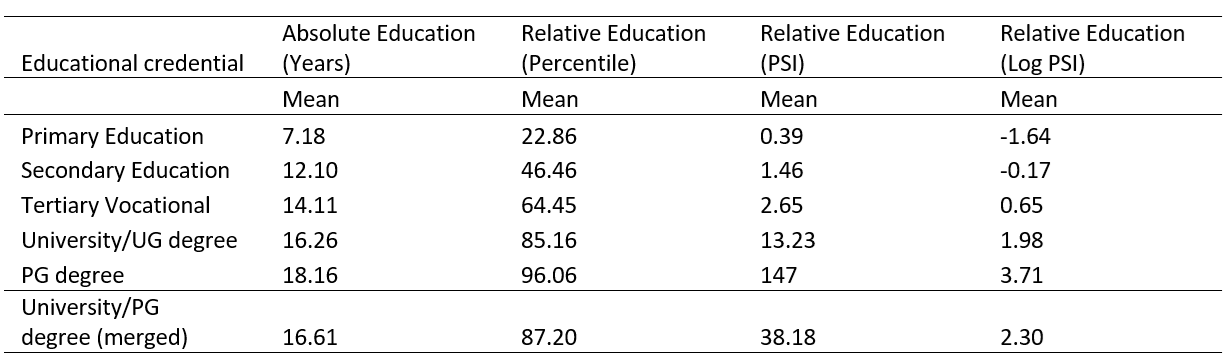

To approximate workers’ relative position in the educational attainment distribution to explain differences in returns to educational credentials, researchers have traditionally used a relative measure of education, operationalized as a rank-based indicator based on the percentile of years of formal schooling. Although this percentile provides valuable insights, it assumes that the relative positions of workers are equal at each point in the educational distribution (Tam, 2016). Instead, we used a positional status index (PSI) to capture the positional dimension of education. This is a monotonic transformation of years of education into a rank order measure that captures the “average number of competitors that were excluded” (ACE) (Tam 2007; 2016). The PSI index predicts rank-based inequality in returns to education, which reflects the competitive structure of the labor markets. The PSI orders workers from the sample in each country-year according to their relative positions at the educational level relative to others. We focus on workers aged 25–35 years, considering this group to be those who are entering or have recently entered the labor market in each country-year.

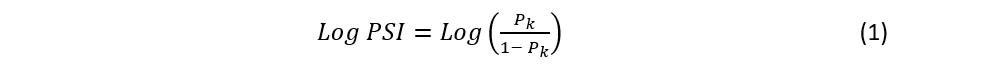

In equation 1, 𝑃𝑘 is the actual percentile in the educational hierarchy, measured from years of education, which represents the proportion of young workers with less than k years of education in each specific country-year cluster. The denominator 1 −𝑃𝑘 captures, then, the proportion of workers above k years of education. Hence, the distances increase across values close to the top of the hierarchy of the educational distribution, capturing the relative scarcity of the educational attainment of an individual, relative to competitors in the labor market. A logarithmic transformation was used to correct the skewness of the original PSI distribution and ease the interpretation as proportional changes, or elasticities (Rotman et al., 2016; Tam, 2007; 2016).

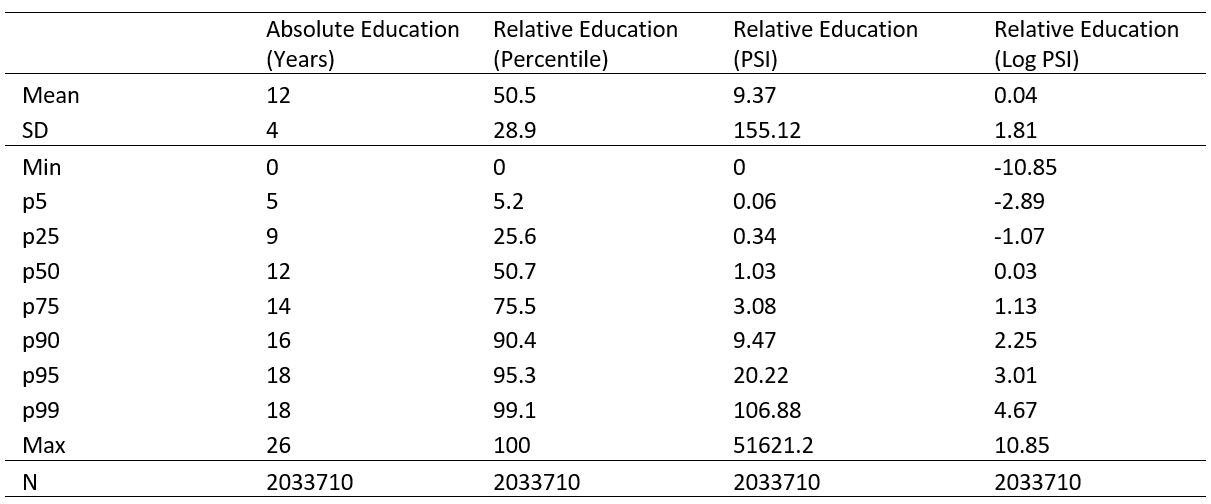

Table 1 presents the descriptive information for all measures of educational attainment used in this study. Table 2 shows the average values of individual indicators of education across the main educational credentials in the Americas.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for educational measures

Source: Luxembourg Income Study (LIS) Database, 1990-2019. Own calculations.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for educational measures in the Americas

Source: Luxembourg Income Study (LIS) Database, 1990-2019.

Note: UG stands for undergraduate degree (university/bachelor’s degree) and PG stands for postgraduate degree (master ’s and PhD). Own calculations.

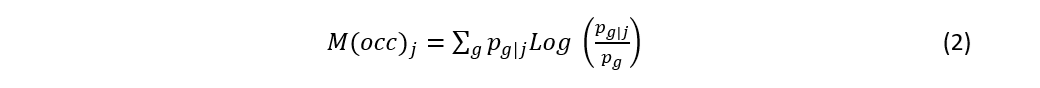

Individual-level variation in the value of educational credentials can have aggregated effects across labor markets, which, in the case of deregulated markets such as in the Americas, may reflect a low clustering of educational credentials across occupations. To approximate the structure of local labor markets across countries, we use the local segregation index for occupations presented in Equation 2, which captures the linkage between educational credentials and occupations (Diprete et al., 2017).

Equation 2 shows the local Mutual Information Index for each occupational group j. The conditional probability of an individual having graduated from the g educational level, given that the individual was recruited in the j occupational group is denoted by 𝑝𝑔|𝑗, and 𝑝𝑔 denotes the unconditional probability of having graduated from the g educational level2. The local segregation index for occupations (M(occ)j) captures the recruitment process and wage setting based on the educational qualifications of workers. This helps us understand the degree of educational selectivity employers exhibit across various occupational groups. We do this within the context of educational expansion at different levels.

The changing value of education: regional and country trends

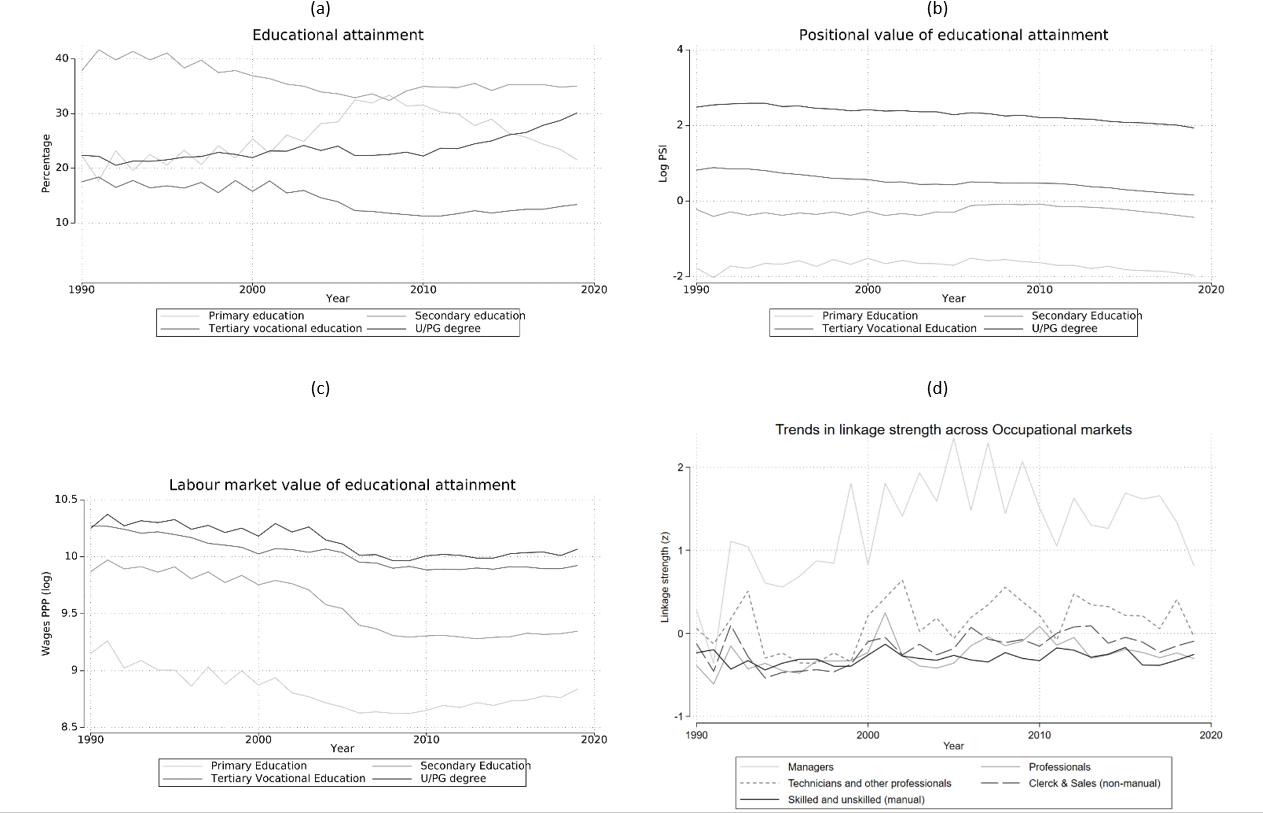

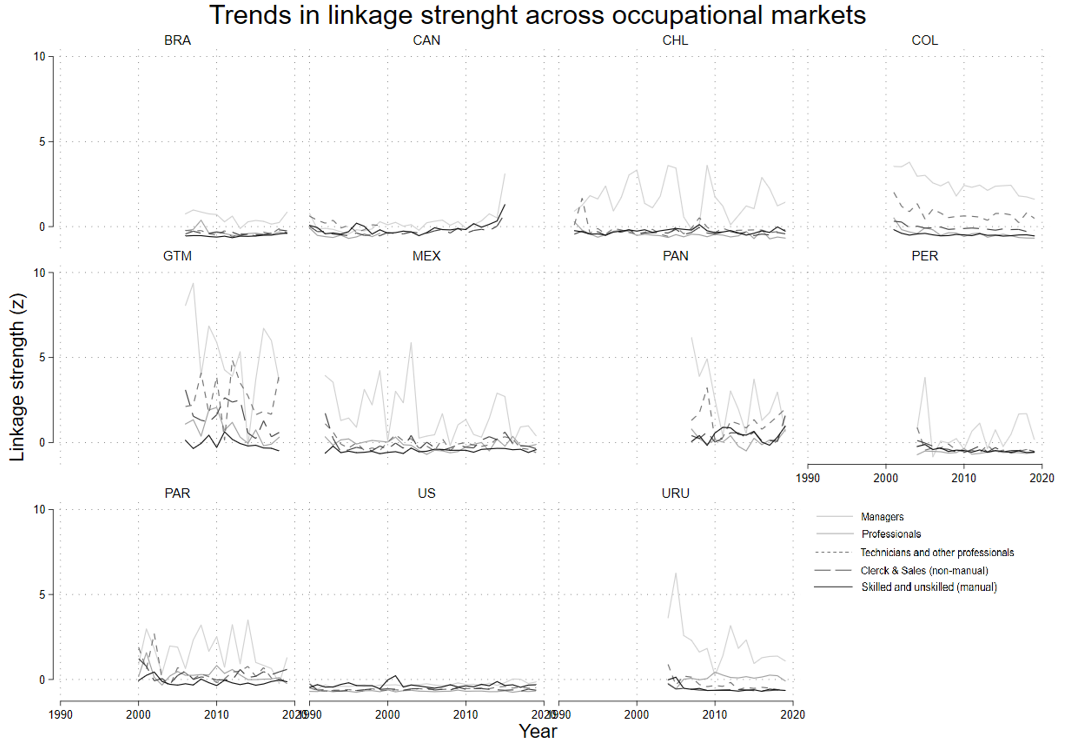

Figure 1 depicts the main trends in educational attainment, labor market value and structural link between educational levels and occupations in the Americas between 1990-2019 among new entrants to the labor market. Panel A portrays the share of educational attainment and Panel B the positional value of education (PSI). Panel C, in turn, shows the market value of educational attainment (log PSI), and Panel D the linkage strength across occupational groups.

Figure 1. Share, positional, market value of educational attainment, and linkage strength of occupational groups in the Americas, 1990-2019

Source: Luxembourg Income Study (LIS) Database, 1990-2019. Sample of workers 25-35 years old. Weighted samples (normalized). Own calculations.

Panel A shows a significant increase in the proportion of young workers with university or postgraduate degrees during the study period. Conversely, those who entered the labor market with primary and secondary education diplomas declined. The relative position of each educational level shows an overall slightly decreasing trend, particularly for those who entered the labor market with post-secondary qualifications (Panel B). In addition, we see structural differences in the average wage levels across educational credentials (Panel C), although higher educational qualifications seem to be less affected. Notably, the wage levels of primary and secondary educated job entrants declined in the early 2000s. Finally, we observed the extent of coupling between educational credentials and occupational markets, which was the highest among managerial and technical occupations (Panel D). The patterns are more heterogeneous, with an apparent increase in the late 2000s across these labor markets.

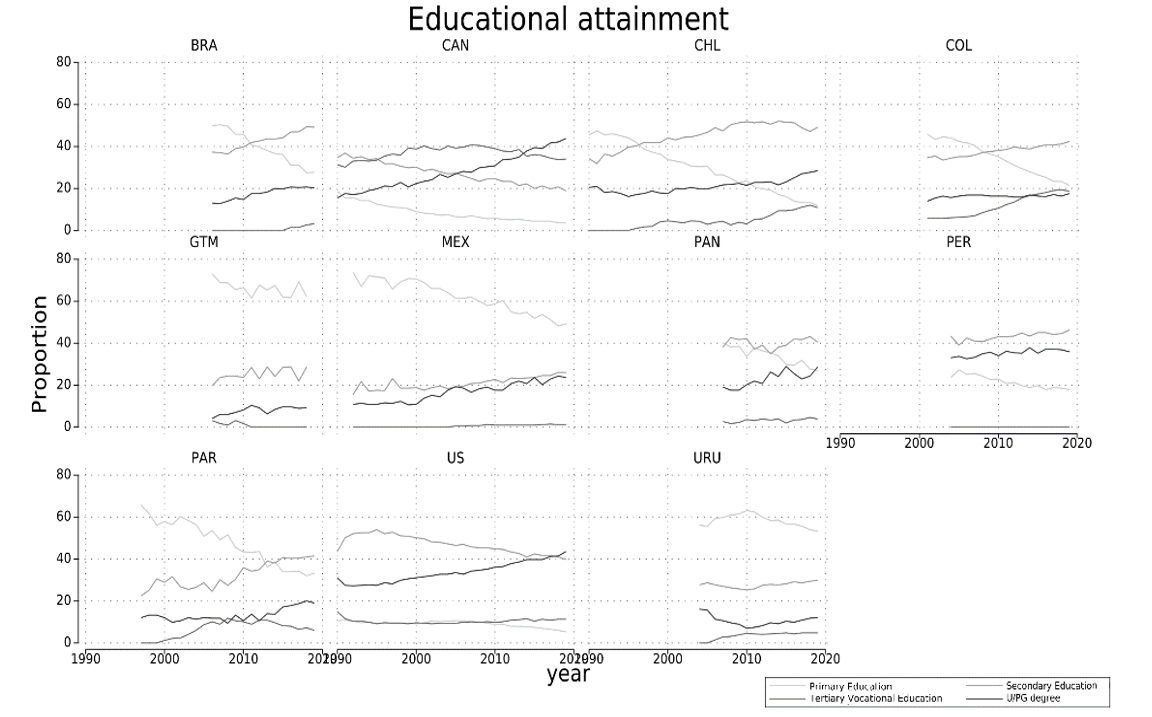

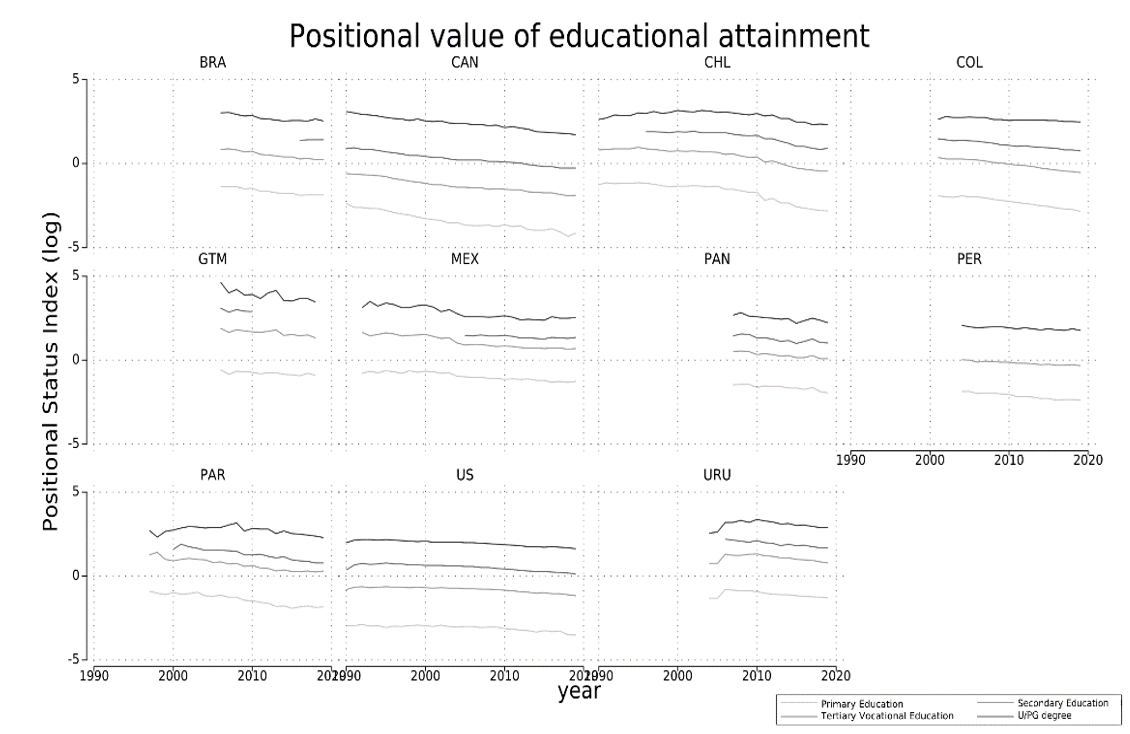

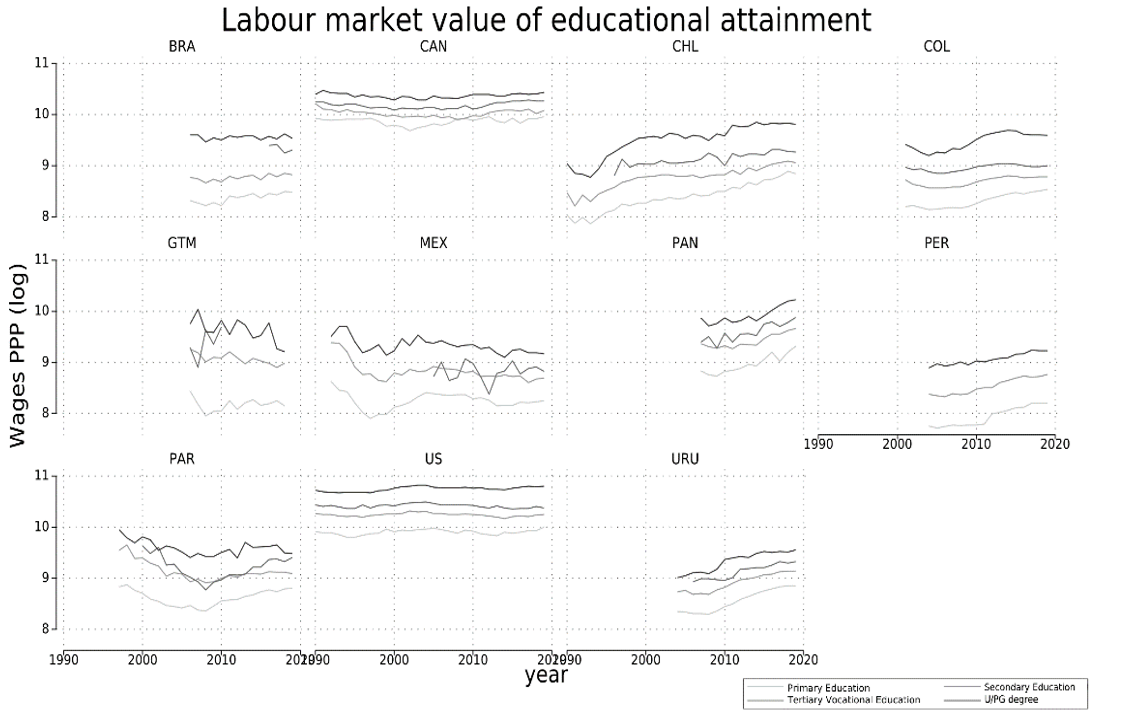

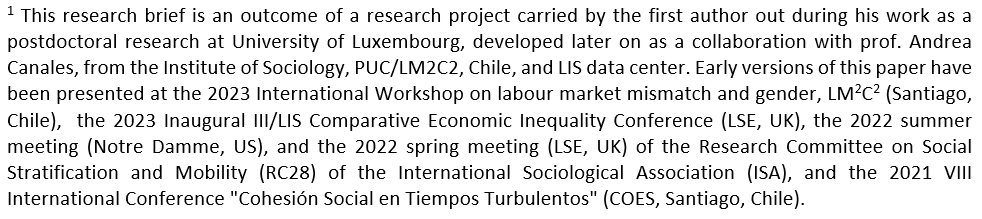

Examining educational expansion trends by country reveals more nuanced processes that are likely connected to each nation’s development stage and economic conditions. While every nation experiences growth in its highly educated workforce, advanced economies, such as the United States and Canada, exhibit a transition from secondary school graduates to those with higher education degrees. By contrast, most Latin American countries experienced a transition from primary to secondary education in the 1990s and the 2000s, with some showing less clear trends or indicating a similar future shift. The positional value of education exhibited a slight overall decline, maintaining clear structural differences (Figure 2 and 3). Similarly, labor market value and credentials linkage, although suggesting an apparent increase among lower educational levels in several countries, show no clear trend as they may be confounded with government policies (Lustig et al., 2016). The educational specificity across occupational groups, also displayed significant heterogeneity over time (Figure 4 and 5).

Figure 2. Trends in educational attainment by country 1990-2019

Source: Luxembourg Income Study (LIS) Database, 1990-2019. Sample of workers 25-35 years old. Weighted samples (normalized). Own calculations.

Figure 3. Trends in positional value of educational credentials by country 1990-2019

Source: Luxembourg Income Study (LIS) Database, 1990-2019. Sample of workers 25-35 years old. Weighted samples (normalized). Own calculations.

Figure 4. Trends in labour market value of educational attainment by country 1990-2019

Source: Luxembourg Income Study (LIS) Database, 1990-2019. Sample of workers 25-35 years old. Weighted samples (normalized). Own calculations.

Figure 5. Trends in linkage of educational credentials across occupational groups by country 1990-2019

Source: Luxembourg Income Study (LIS) Database, 1990-2019. Sample of workers 25-35 years old. Weighted samples (normalized). Own calculations.

Nevertheless, it is plausible to consider whether counterbalancing effects between the positional value of education and the way in which educational credentials are demanded across occupations can unravel patterns of wage inequalities that are more pronounced than in terms of cumulative years of education. The labor markets across countries in the region are either less structured or unstructured. Employers’ coordination follows the logic of the market, meaning that employers find lower or no limits to rewards achieved or ascribed (unobserved) interpersonal differences. The absence of social partners to establish formal educational requirements and, hence, wage-setting coordination3, may rely on both formal, such educational credentials, and relatively scarce informal entry requirements, such indicators for on-the-job training, or sociocultural suitability for certain occupations (Jackson, Goldthorpe and Mills, 2005; Di Stasio et al., 2016; Rivera, 2012; Weeden, 2002).

Discussion and conclusion

These analyses suggest no direct or linear relationship between educational expansion and educational credentials’ positional and monetary values. In the context of liberal governments in North and South American countries, labor markets in these areas are likely to create demand-side incentives. Employers would be inclined to value the competitive edge of job candidates, which could encompass individual productivity differences stemming from both acquired and inherent traits, particularly in a context of expanding educational opportunities. The weakly developed vocational training system and highly deregulated wage-setting coordination would also create incentives from the supply side among jobseekers to overeducate as a result of credential inflation. Nevertheless, the crucial factor here is occupations. Occupational categories represent the level at which allocation processes take place, specifically the matching or mismatching of occupational positions.

In this study, we investigated occupations by analysing the clustering of educational credentials within occupational groups (namely, educational specificity). We examined the intensity of educational credential selectivity across employers in different occupational groups, given the context of educational expansion at different levels. Our findings revealed an increasing reward of positional advantages of education across highly selective occupational groups despite the pressures to lower the wage levels associated with the increasing influx of graduates in the labor market. In a forthcoming study, we aim to build upon these findings by examining the structure of local labor markets across countries as the linkage between educational credentials and occupations as proposed by Diprete et al. (2017).

In advancing these findings, we contribute to the literature with this unique effort in taking a cross-national perspective in the Americas, an understudied case. The distinctive institutional characteristics of North and South America offer an ideal setting for gathering consistent data on the interplay between occupations, educational achievement, and labor market outcomes. While we acknowledge the limitations of using LIS harmonized datasets instead of more detailed, country-specific sources, we believe our approach has merit to easily show a general finding of trends across countries. By pooling the Americas together, it became evident that particularly the secondary level graduates found themselves put under strain in the early 2000s. Nevertheless, a comprehensive examination of the role of education in the specific regional context in which we based our analyses, could significantly contribute to the existing school-to-work transition literature by focusing on the relationship between education’s positional aspect and labor market structures.

References

| Autor, D. and Handel, M. J. (2013). Puttting tasks to test: human capital, job tasks, and wages. Journal of Labour Economics, 31, 59–96. |

| Barrientos, A. (2009). Labour markets and the (hyphenated) welfare regime in Latin America. Economy and Society, 38(1), 87-108. |

| DiPrete, T. A., Eller, C. C., Bol, T., & Van de Werfhorst, H. G. (2017). School-to-work linkages in the United States, Germany, and France. American journal of sociology, 122(6), 1869-1938. |

| Di Stasio, V., Bol, T., & Van de Werfhorst, H. G. (2016). What makes education positional? Institutions, overeducation and the competition for jobs. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 43, 53-63. |

| Fiszbein, A. (2005). Beyond truncated welfare states: Quo vadis Latin America?. Washington, DC: The World Bank. |

| Jackson, M., Goldthorpe, J. H., & Mills, C. (2005). Education, employers and class mobility. Research in social stratification and mobility, 23, 3-33. |

| Jahn, D. (2014). Changing of the guard: Trends in corporatist arrangements in 42 highly industrialized societies from 1960 to 2010. Socio-Economic Review, http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwu028 |

| Levy, S., & Schady, N. (2013). Latin America’s social policy challenge: Education, social insurance, redistribution. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 27(2), 193-218. |

| Lustig, N., Lopez-Calva, L. F., Ortiz-Juarez, E., & Monga, C. (2016). Deconstructing the decline in inequality in Latin America. In Inequality and growth: Patterns and policy (pp. 212-247). Palgrave Macmillan, London. |

| Marteleto, L., Gelber, D., Hubert, C., & Salinas, V. (2012). Educational inequalities among Latin American adolescents: Continuities and changes over the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s. Research in social stratification and mobility, 30(3), 352-375. |

| OECD (2023). https://data.oecd.org/eduatt/population-with-tertiary-education.htm. |

| Rivera, L. A. (2012). Hiring as Cultural Matching the Case of Elite Professional Service Firms. American Sociological Review, 77, 999–1022. |

| Rotman, A., Shavit, Y., & Shalev, M. (2016). Nominal and positional perspectives on educational stratification in Israel. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 43, 17-24. |

| Schincariol, V. E., Barbosa, M. S., & Yeros, P. (2017). Labour trends in Latin America and the Caribbean in the current crisis (2008–2016). Agrarian South: Journal of Political Economy, 6(1), 113-141 |

| Tam, T. (2007, May). A paradoxical latent structure of educational inequality: Cognitive ability and family background across diverse societies. In conference on social inequality and mobility in the process of social transformation, international sociological association RC28. |

| Tam, T. (2013, October). Analyzing education as a positional good: Categorical regression without arbitrary identification. In The European Consortium for Sociological Research’s 2013 Conference, Tilburg University. |

| Tam, T. (2016). Academic achievement as status competition: Intergenerational transmission of positional advantage among Taiwanese and American students. Chinese journal of sociology, 2(2), 171-193. |

| UNESCO Institute for Statistics. (2012). International standard classification of education: ISCED 2011. Montreal: UNESCO Institute for Statistics. |

| Weeden, K. A. (2002). Why Do Some Occupations Pay More than Others? Social Closure and Earnings Inequality in the United States. American Journal of Sociology, 108, 55–101. |