Issue, No.31 (September 2024)

Analyzing Migrant Wealth Gaps in Cross-National Perspective Using LWS Data*

Wealth inequality literature has recently expanded by adopting a comparative approach. However, wealth stratification by migration background has been slower to follow this trend.

Adding wealth to research on migration and host-country integration would be of utmost importance. First, the existence of substantial gaps in wealth accumulation and asset participation might be taken as an indicator of economic and social exclusion (Agius Vallejo and Keister, 2020). Second, as wealth is a fundamental stratifier of life chances (Killewald et al., 2017), differences in wealth accumulation translate into inequalities in different domains, across various life stages of individuals, and over generations.

The lamented lack of comparative research on wealth stratification by migration background is largely due to data availability issues. In this contribution, I will (a) discuss the use of the harmonized Luxembourg Wealth Study (LWS) as a unique resource for comparative research on wealth stratification by migration background, and (b) provide a recent descriptive overview of wealth stratification across multiple countries.

Summary of previous research

To my knowledge, four studies have investigated cross-country household wealth differences by migratory background. Mathä et al. (2011) examined migrant wealth gaps (MWG) in Germany, Italy, and Luxembourg, utilizing early releases of LWS data. Bauer et al. (2011) compared Australia, Germany, and the United States using national samples, while Abdul-Razzak et al. (2015) focused on the United States and Italy, also using national samples. Ferrari (2020) investigated MWG in 17 European countries, aggregated into four macro-areas, using SHARE data on populations aged 50 and over.

These studies consistently show that a substantial migrant wealth gap exists, which is robust across most of the wealth distribution. A significant portion of this disadvantage among migrant households is attributed to lower homeownership rates compared to natives. Despite these commonalities, there are large differences in the magnitude of MWG. For instance, Bauer et al. (2011) reported that the MWG at the mean ranged from approximately 9,000 US dollars in Australia to around 150,000 US dollars in the United States.

In seeking to explain the sources of MWG, and similar to research on income differentials, these studies primarily focused on compositional differences between natives and migrants. Decomposition methods were applied to identify the influence of sociodemographic (e.g., age, household composition) and socioeconomic (e.g., educational attainment, income, occupation) characteristics on the observed MWG.

Wealth disparities linked to migratory backgrounds are often examined within the broader context of racial inequalities, with the white-black wealth gap being one of the most extensively studied topics in wealth literature (Conley, 2010). Consequently, the literature tends to distinguish between primary factors – such as ethnicity – that affect both natives and migrants, and secondary factors – such as discrimination – that impact migrants specifically. This distinction is relevant to comparative studies of migrants gaps, as observed gaps may also reflect underlying ethnic wealth disparities.

What can be done using the Luxembourg Wealth Study

The LWS cross-national harmonized wealth database provides a unique opportunity to conduct comparative research on the assets and debts of migrant populations, as well as comparisons between migrants and natives. Additionally, the database includes a range of migration-related individual characteristics. With its combination of high-quality data on migration, wealth, and sociodemographic and socioeconomic characteristics, the LWS database is particularly well-suited for comparative studies on this topic.

Of the 21 countries included in the LWS database, 16 countries have immigration data available for at least one year. Covering survey years from 2004 to 2022, these countries are: Australia, Austria, Chile, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Greece, Italy, Luxembourg, Norway, Slovakia, Slovenia, South Africa, Sweden, and the United States. In contrast, Canada, Japan, South Korea, Spain, and the United Kingdom have no immigration data available in any survey years. Overall, the use of LWS data allows for cross-sectional analyses of MWG in several European countries and other regions, enabling comparisons across national contexts with vastly different institutional settings that influence both wealth accumulation opportunities and social and economic barriers for immigrants.

Out of 103 country-years, immigration data is available for 60 country-years. Longitudinal analysis, in the form of repeated cross-sectional studies spanning at least a decade, would be possible for eight countries. Some countries—such as Australia, Italy, Norway, and Denmark—are particularly well-suited for this purpose. Given the high number of available country-years, precise estimates of the evolution of MWG can be obtained for this subset of countries. This would allow for investigating the influences of changes in immigrant demographics (e.g., aging), immigration policy (e.g., reforms in citizenship laws), and socioeconomic crises.

While restricted only to some country-years combinations, the additional variables in the migration section are key for an in-depth characterisation of migrants. Two of them are particularly relevant. First, by using years of residence in the country it is possible to make comparisons between natives, permanent and temporary migrants as well as to model the magnitude of the convergence between migrants’ and natives’ wealth accumulation trajectories over the age distribution (Semyonov and Lewin-Epstein, 2022). Second, by using the country (or area) of birth, it is possible to better understand the diversity of migrant structure in each country and also to make comparisons between migrants coming from the same country (or area) of birth across different countries. While years of residence and area of birth are largely available in LWS, the information on citizenship of the host country as well as ethnicity is available for a small subset of countries, making the inferential capacity of the analysis on this matter much more limited. Finally, the use of behavioral/attitudinal variables could have great potential, given the oftentimes mentioned relevance of attitudes in driving differences between natives and migrants in wealth attainment.

An overview of the potential of LWS would be incomplete without acknowledging its limitations. Despite the growing numerical and societal significance of second-generation migrants and their integration worldwide, information on migrant generation is directly available in LWS for only two countries: Germany and Norway allow for identifying second-generation migrants.

Some evidence on migrant wealth (and debt) gaps across countries

Using the information from LWS, I present descriptive evidence on wealth and debt disparities based on immigration background. This analysis utilizes 14 national cross-sectional datasets, primarily from 2016 to 2018, with the notable exception of the United States, for which the only available dataset is from 2022. The analysis is based on a sample of approximately 500,000 households, where the head of the household is between 20 and 75 years old.

I define as “immigrant” any household where the head of the household is reported as such.1 For wealth-related variables, I considered harmonized wealth aggregates, including disposable net worth, real estate assets, financial assets (excluding pensions), total debts, debts related to real estate, and debts on non-housing liabilities. All values are expressed in 2017 US dollars adjusted for purchasing power parity (PPP).

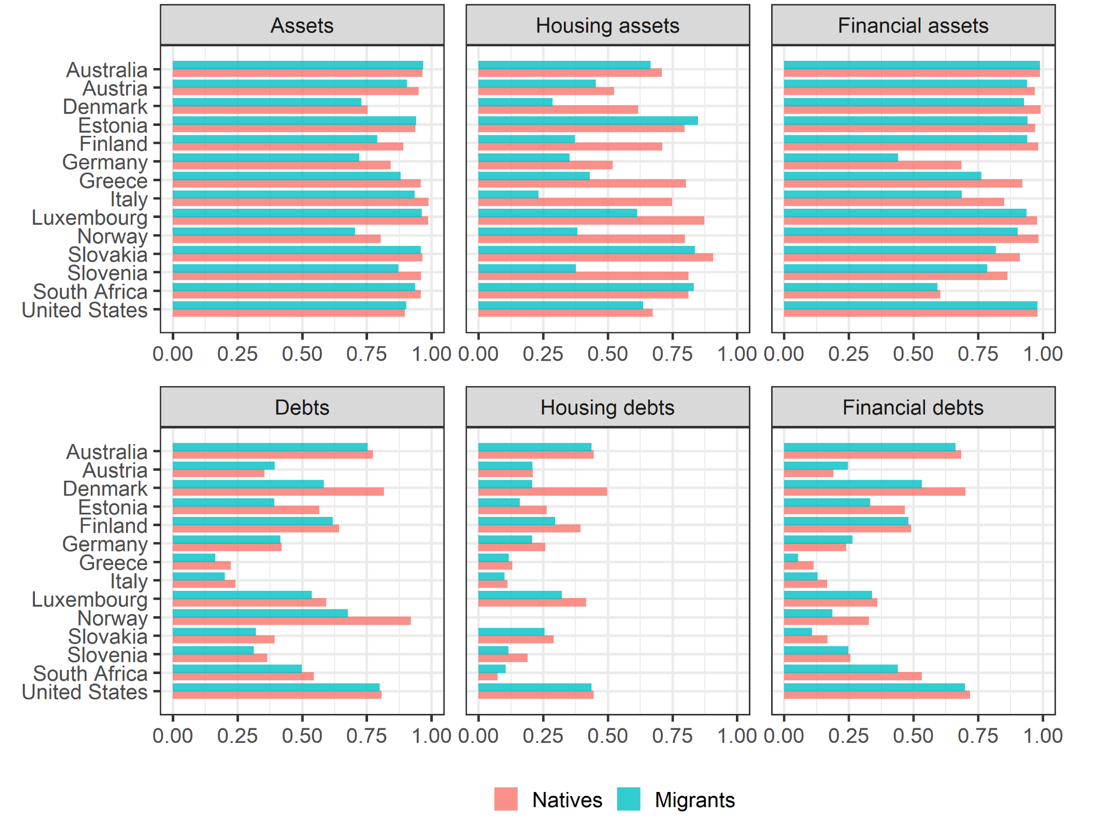

Figure 1 – Assets and debts participation rates. 14 countries, 2016/2018.

Figure 1 illustrates asset participation rates, representing the percentage of native and migrant populations holding any form of assets or liabilities. All countries exhibit high participation rates, consistently above 75%. However, in the vast majority of countries, natives are more likely to possess wealth compared to migrants. The most significant differences in asset participation are observed in Germany, Finland, and Norway. Conversely, in countries like Australia and the United States, the differences are minimal.

A closer inspection of housing and financial asset participation rates reveals varying trends across wealth components. While financial asset participation rates are generally similar between the two groups, significant disparities exist in the ownership of real assets. This finding aligns with previous research on the role of homeownership in wealth stratification. Notably, this is particularly evident in European countries such as Finland, Denmark, Italy, and Norway, despite their differing housing systems.

Regarding debt, despite considerable cross-country heterogeneity in overall debt access, natives are generally more likely to hold debt than migrants. Differences are negligible in countries such as Australia and the United States and are relatively small overall, except in Finland and Norway. Similar to wealth, disparities in debt are primarily driven by liabilities related to real estate rather than non-real-estate assets.

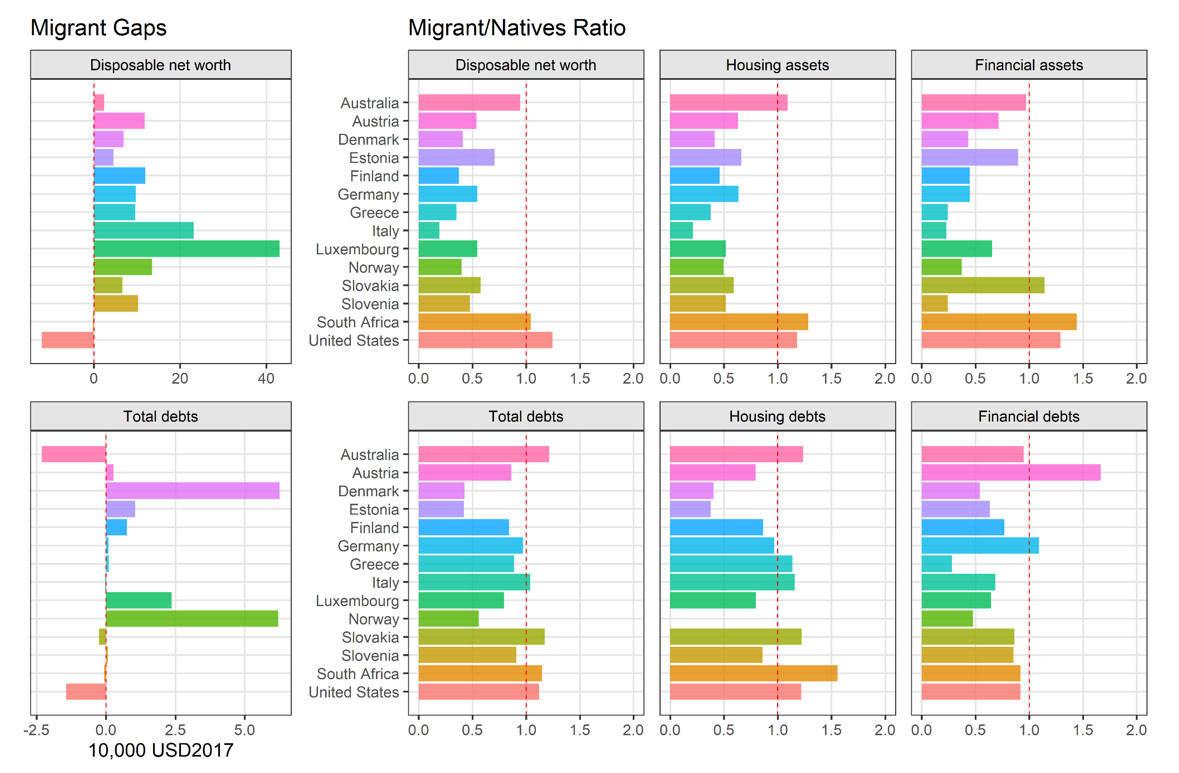

Figure 2 – Migrant gaps and migrants/natives ratios for wealth and debt. 14 countries, 2016/2018.

Figure 2 presents descriptive statistics based on the monetary values of wealth and debt variables. The left panel displays the migrant gaps in disposable net worth and total debts at the means, expressed in increments of 10,000 US dollars. The right panel shows the ratio between migrants’ and natives’ wealth and debts, with a further breakdown by housing and financial components.

Regarding wealth gaps, 12 out of the 14 countries exhibit a wealth gap disadvantageous to immigrants, averaging around 100,000 US dollars, with a maximum gap of approximately 400,000 US dollars in Luxembourg. Interestingly, the wealth gap is about 20,000 US dollars in Australia, null in South Africa, and even negative in the United States.2 The immigrant-to-native wealth ratios further illustrate that, in most countries, immigrants own about half the wealth of natives. Notably, these ratios tend to be smaller for housing wealth compared to financial wealth, corroborating the importance of homeownership in wealth inequality.

As for debt gaps, the differences are smaller in magnitude than wealth gaps. In six out of the 14 countries, natives carry more debt than migrants, with an average difference of about 10,000 US dollars and a maximum of 60,000 US dollars in Norway and Denmark. Interestingly, in Australia and the United States, immigrants are more indebted than natives. Given the significant cross-country variation in debt access, ratios are a more reliable measure for comparison: in most countries, migrants and natives hold similar amounts of debt.

Concluding remarks

As migrant populations increasingly reach retirement age, the urgency of research on wealth disparities has grown, particularly in countries where privately accumulated economic resources are crucial for consumption during retirement.

This contribution highlights LWS as a valuable database for advancing our understanding of wealth inequality and stratification related to migration. While existing research has focused on a limited number of countries, LWS allows for broader analysis across a more extensive range of countries and time periods, with data spanning several years and, in some cases, more than a decade.

By using LWS data for 14 countries, I found evidence that migrants hold less wealth than natives in almost all countries, while in only a few cases are immigrants more indebted than natives. Although this disadvantage is widespread, differences across countries exist in both the magnitude of disadvantages and wealth component (real or financial) driving the disadvantages.

Exploring cross-country differences in migrant wealth and debt gaps is a necessary first step; however, the most compelling aspect lies in understanding the underlying determinants of these disparities, both at the individual and contextual levels. The extensive data provided by LWS can enable future researchers to make significant advances in the related literature.

* This article is an outcome of a research visit carried out in the context of the (LIS)2ER initiative which received funding from the Luxembourg Ministry of Higher Education and Research.

1 Given that immigration background is provided at the individual level, it is possible to further differentiate households by distinguishing mixed households in which both migrants and natives are present.

2 As mentioned earlier, US22 is the first and only dataset for the United States that includes information on migratory background. Since my estimates differ somewhat from those found in previous literature, it will be important to reassess the robustness of these findings as more data becomes available in future releases.

References

| Abdul-Razzak, N., Osili, U. O., & Paulson, A. L. (2015). immigrants’ access to financial services and asset accumulation. In Handbook of the economics of international migration (Vol. 1, pp. 387-442). North-Holland. |

| Agius Vallejo, J., & Keister, L. A. (2020). Immigrants and wealth attainment: migration, inequality, and integration. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 46(18), 3745-3761. |

| Bauer, T. K., Cobb-Clark, D. A., Hildebrand, V. A., & Sinning, M. G. (2011). A comparative analysis of the nativity wealth gap. Economic Inquiry, 49(4), 989-1007. |

| Conley, D. (2010). Being black, living in the red: Race, wealth, and social policy in America. University of California Press. |

| Ferrari, Irene. (2020). The nativity wealth gap in Europe: a matching approach. Journal of Population Economics, 33(1), 33-77. |

| Killewald, A., Pfeffer, F. T., & Schachner, J. N. (2017). Wealth inequality and accumulation. Annual Review of Sociology, 43(1), 379-404. |

| Mathä, T. Y., Porpiglia, A., & Sierminska, E. (2011). The immigrant/native wealth gap in Germany, Italy and Luxembourg. ECB Working Paper, 1302 |

| Semyonov, M., & Lewin-Epstein, N. (2022). The wealth gap between ageing immigrants and native-born in ten European countries. Czech Sociological Review, 57(6), 639-660. |