Issue, No.32 (December 2024)

Wealth and education of single-parents households in the light of different education policies.*

Introduction

The share of single-parent households has been increasing in most countries since 1980 (Nieuwenhuis & Maldonado, 2018). Research indicates single-parent households have lower levels of disposable income and wealth in comparison to two-parent households (Sierminska, Smeeding, and Allegrezza 2013; Sierminska 2018; Morelli et al. 2022). Maldonado and Nieuwenheuis (2015) demonstrate that in 18 OECD countries, between 1978 and 2008 single-parent households were consistently more likely to experience poverty than two-parent households. Single-parent households also possess less than 50% of wealth compared to their coupled counterparts (Sierminska, 2018).

Earning a higher income makes saving easier, and saving is necessary to build wealth. It is a well-known fact that individuals with a high level of education earn more than those with a medium level of education (secondary/high school) and this phenomenon is referred to as the “college premium”. In the majority of EU countries, the average wage is more than twice as high for those with a high level of education. A similar pattern is observed in the US: the more educated you are, the higher is your salary (Wolla & Sullivan, 2017). However, this positive impact of education on wealth may be disrupted in countries with a private education financing system due to high education costs (for US see Scott et al. 2022, 2023, Emmons et al. 2019).1

The financing of education, whether public or private, not only affects access to education and social inequalities but also has broader socio-economic implications. In this analysis, we investigate the differences in education of single parents across countries and the resulting variations in household wealth among single- and other household types, especially couple parent households. Our main hypothesis is that in countries with a prevalent private education finance system, households will possess less wealth due to the high costs of education. This could disproportionately affect single-parent households compared to their dual-parent counterparts given their lower flexibility in work schedules (among other factors), which potentially limits their ability to fully benefit from higher education and advance professionally while balancing personal responsibilities. Our analysis is not causal, yet brings to light additional disparities existing among households. We analyse this in more detail in our working paper.

The education and wealth of single parents across countries (with different education finance systems)

Using LWS data, we examine a unique set of thirteen countries with one wave of data for the 2016-2019 period. We focus on the following: Southern Europe (Greece 2018, Italy 2016 and Spain 2017), Western Europe (Germany 2017, Austria 2018, Luxembourg 2018), Nordic countries (Finland 2016, Denmark 2019, Norway 2019), and Anglo-Saxon countries (Australia 2018, Canada 2016, the UK 2019 and the US 2019). The distinction between countries with free and paid higher education finance systems is made according to the OECD classification (OECD, 2019). The countries that operate a paid system of higher education are all located in the Anglo-Saxon region, namely Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom and the United States. These countries have high tuition fees and well-developed student support systems. The countries with free higher education can be divided into two subgroups. The first subgroup comprises countries with no or low tuition fees and generous student support systems, including the Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland and Norway) and Luxembourg.2 The second subgroup includes countries with no or low tuition fees and less-developed student support systems, such as Austria, Italy, Spain, Germany and Greece.2 For the purposes of this study, four distinct household types are defined:3

- single households: one adult (1-person household);

- single-parent households: one adult and at least one child (younger than 18);

- couples with children: two adults (married or cohabiting) and at least one child (younger than 18);

- couples without children: two adults (married or cohabiting).4

Our main variable of interest is net worth.5 Net worth is defined as the sum of financial and non-financial assets minus liabilities (secured and unsecured). Our measure of net worth also includes life insurance and voluntary individual pensions for all countries for which data are available.6 We top code wealth at the 99th percentiles and bottom code at the 1st percentile. The monetary values are converted to 2017 US dollars using the 2017 consumer price indices and 2017 USD PPP published on the LIS website.7

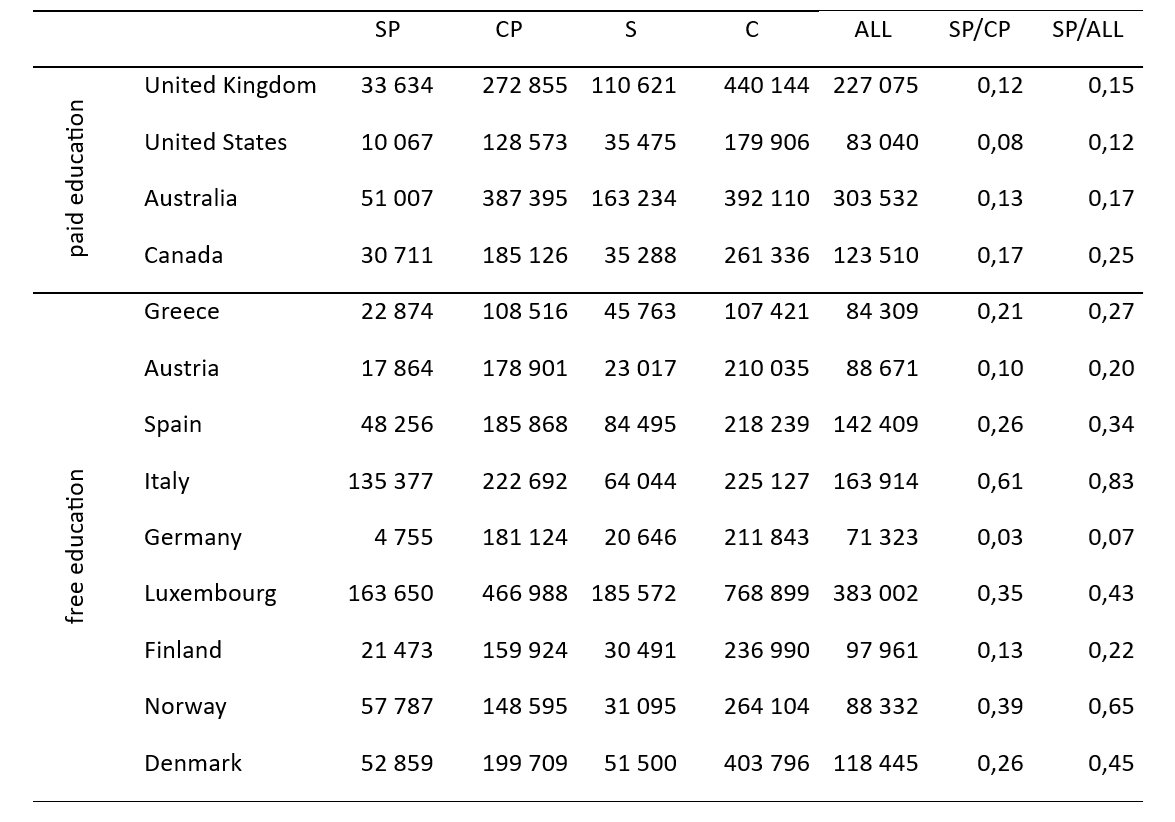

Figure 1. The educational attainment of single parents for selected countries

Source: Own calculation based on the LWS.

Notes: Lighter bar colors indicate countries with a paid education finance system (the UK, Australia, the US, Canada). These countries have high tuition fees and well-developed student support system. Darker bar colors represent countries with a free education finance system (Austria, Italy, Spain, Germany, Greece, Finland, Luxembourg) These can be divided into those with (1) generous student support systems (Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland and Norway) and Luxembourg); (2) less-developed student support systems (Austria, Italy, Spain, Germany and Greece).

Figure 1 presents the educational attainment of single-parent households distinguishing between two levels of education: low and high.8 The countries are sorted according to two criteria. Initially, a distinction is made between countries with a paid and a free education system. Subsequently, the countries are ordered in ascending order according to the level of higher education attained by single parents. In countries with a paid higher education system, single parents are, on average, better educated than in countries with a free education finance system. In countries with paid higher education, the proportion of single parents with a high level of education is the lowest in the United Kingdom (28%) and the highest in the United States, Australia and Canada (42%, 44% and 63% respectively). In countries where higher education is provided free of charge we observe an interesting pattern. The lowest proportion of high-educated single parents is observed in countries with less-developed student support education system: Greece, Austria, Spain, Italy, Germany, Luxembourg (10%, 16%, 17%, 20%, 22% and 38% respectively) and the highest in Finland, Norway and Denmark (40%, 41 and 42% respectively).

Interestingly, in countries with a generous student support system (regardless of the higher education finance system) we observe a similar fraction of single parents with high education – around 30% – 40%, with the distinction of Canada, where more than 60% of single parents are highly educated. It is worth noting that in Spain more than half of single parents have the lowest level of education, which is almost twice as many as in other countries.

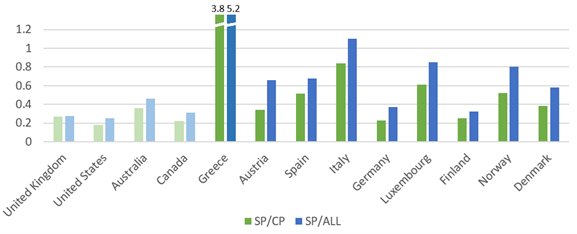

Table 1 Median wealth levels (in USD)

Notes: Own calculation based on the LWS.

Turning to wealth levels, Table 1 presents the median wealth ratios for all household types (All), singles (S), single parents (SP), couples (C) and couple parents (CP). A number of noteworthy observations emerge from the data. Firstly, in most countries, apart from Italy, Finland and Norway, single parents consistently exhibit the lowest median net wealth compared to other household types. In Italy, Finland and Norway singles have the lowest median wealth. Secondly, the highest median wealth for all household types is observed in Luxembourg, Australia and the United Kingdom, whereas the lowest median net wealth is observed in the US, Greece, Austria, Germany, Finland and Denmark (below 100,000 USD). Thirdly, in almost all countries, the wealthiest household type are couples (apart from Greece). Couples have at least 1.7 times more net wealth (for Italy) and even 10 times more (UK, US, Austria, Germany and Finland) than single parents. Couples with children have higher median wealth than singles and single-parents but not more than couples (with the distinction of Greece, where couples with children poses the highest amount of net wealth).

We examine whether a similar disparity in median net wealth is observed between households with high levels of education and whether there is any pattern characteristic of countries with paid and free education systems. Figure 2 presents the ratio of median net wealth between highly educated single parents and couples with children and all households. The green bars represent the wealth ratios between single parents and all household types, while the blue bars represent the wealth ratios between single and couple parents.

Figure 2. The median ratio of wealth for highly educated single parents

Source: Own calculation based on the LWS.

Notes: Lighter bar colors indicate countries with a paid education finance system (the UK, Australia, the US, Canada). Darker bar colors represent countries with a free education finance system (Austria, Italy, Spain, Germany, Greece, Finland, Luxembourg, Norway and Denmark).

Figure 2 illustrates discernible patterns. Primarily, single parents exhibit a lower median net wealth than couples with children and all other household types in countries with paid education finance systems. This is also the case in countries with a free education finance system, with the exception of Greece and Italy. In Greece, single parents demonstrate a comparatively higher median net wealth than couples with children and all other households. Conversely, in Italy, single parents exhibit a median net wealth that is equivalent to 110% that of all other households and 84% of couple households.

Second, countries with high tuition fees (light green and light blue) exhibit a lower wealth ratio between single and couple parents and single parents and all household types in comparison to countries with no or low education fees (intense blue and intense green, with the exception of Germany and Finland). In other words, in countries where tertiary education is remunerated, single parents with a high level of education possess approximately 33% of the total wealth of all household types. This ratio doubles to 67% in countries with a free tertiary education system (with no or low tuition fees).

It is important to note that there is considerable heterogeneity in the ratios of median wealth in countries with free education finance systems. In countries with free education and less-developed student support systems (Austria, Italy, Spain), highly educated single parents possess approximately 56% of the wealth of dual-parent households and 81% of all households. A contrasting pattern is evident among countries with free education and well-developed student support systems. In Finland and Denmark, the ratio of wealth held by single parents is comparable to that observed in countries with a paid education system, at 32% of the wealth of dual-parent households and 45% of all households, respectively. The net wealth ratios in Luxembourg and Norway are higher and comparable to those observed in countries with less developed student support systems (57% of the wealth of dual-parent households and 83% of all households). The cases of Greece and Germany merit particular attention. In the former, highly educated single parents are the wealthiest household type. In the latter, there is a marked disparity in median net wealth between single parents and couples with children and single parents and all households, despite the country’s relatively low tuition fees and less-developed student support system. This ratio is comparable to that observed in countries with a paid education system.

Thus, to summarize, the discrepancy in median net wealth is less pronounced among households with higher levels of education. In countries with a paid education system, single parents account for an average of 8% (in the United States) to 17% (in Canada) of the net median wealth of couples with children (Table 1). When only higher-educated single parents are considered, the ratio increases to approximately 18% (in the US) to 36% (in Australia). Similarly, the ratio of median net wealth between single parents and all households almost doubles if only higher-educated households are taken into account. A similar pattern is observed in countries with free education systems, where the wealth disparity in median net wealth is lower among higher-educated households.

Discussion:

Single parents are on average better educated in countries with a paid education finance system. The lowest proportion of single parents with a high level of education can be observed in countries where tuition fees are either absent or low, and where the student support system is less developed. Examples of such countries include Austria, Italy, Spain, Germany and Greece. In all countries with a paid education system (Anglo-Saxon countries), single parents have the lowest median wealth. This is also the case in Southern Europe and the Nordic countries, where the lowest median net wealth is observed among single parents. In all countries except Greece, couples exhibit the highest wealth. In countries with well-developed education support systems and free education finance systems, higher disparities in wealth between single and couple parents are observed, as well as a higher share of individuals with higher education.

The data reveal that in countries with a less-developed student support system, such as Austria, Luxembourg, Norway and Southern European countries (Greece, Italy and Spain), there is the lowest disparity in median net wealth between high-educated single and couple parents and all households. In Greece, households with at least one member who has completed higher education have a higher median net wealth than couples with children and all other households. Conversely, in Germany, Finland, Denmark and countries in the Anglo-Saxon tradition, the highest disparities in median net wealth are observed.

A number of factors contribute to the shape and trajectory of wealth in each country. These include economic factors such as social benefits, the education system, the tax system, institutions, as well as private factors such as race, migration history and family/marital history. In the United States, for instance, the expense of education is considerable, while social benefits are subject to asset testing. Consequently, single parents at the lowest end of the socioeconomic spectrum are required to liquidate their assets before becoming eligible for benefits. The European Union, on the other hand, offers a more generous approach. However, it is evident that there is a considerable degree of disparity in wealth between single and couple parents in countries with free education finance systems. In countries with a well-developed student support system, disparities in wealth are more pronounced than in countries with less-developed student support systems. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first analysis to focus on the education and wealth inequalities between single parents and other household types in countries with free and paid education finance systems, which shows a complex relationship between the two depending on the institutions. As our analysis is not causal, further analysis on the education finance system and its impact on wealth and education inequalities is required.

* This article is an outcome of a research visit carried out in the context of the (LIS)2ER initiative which received funding from the Luxembourg Ministry of Higher Education and Research.

1 The cost of education in the US has risen more than inflation since the 1990s, indicating that education costs are exceptionally high. Currently, 43 million Americans rely on loans to finance their education. The student loan debt has surpassed $1.77 trillion, undoubtedly impacting wealth accumulation.

2 In the OECD report, “Education at Glance 2019,” Luxembourg, Germany, and Greece are not assigned to specific country groups. The 2024 edition of “Education at Glance” indicates that 79% of students in Germany do not benefit from the student support system, which includes scholarships and loans. In Greece, only one in eight secondary school graduates with good grades apply for scholarships. Consequently, we have classified these countries as having less-developed student support systems.

3 The aforementioned household types are defined using the variables describing the household composition (hhtype) and marital status (marital). The term ‘single parent’ is used to denote a person whose household composition is one adult and at least one child, and who is not currently married or in a union. We focus on the working age population till age 65.

4 It should be noted that the focus of this study is on households with children under the age of 18. Consequently, the analysis excludes any expenditure on tertiary tuition by parents. This is a crucial assumption, as parents do contribute to their children’s higher education spending. Report “How Americans pay for college” conducted by Sallie Mae shows that in 2019 parents income and savings cover on average 44% pays for college and extra 8% was covered by parent borrowing, what translates in yearly spending equal to approx. $15,600 ($13,072 + $2,538). Furthermore, this article does not address the differences in net worth between different household types with children due to parent education spending.

5 One of the limitations of our study is the fact that we do not know the period of limitations for wealth accumulation of most singles, as compared to the couple households. In other words, the length of time they could have been jointly accumulation with a previous partner preceding their single status. We also do not know the varying role of inherited/gifted wealth reeived from others.

6 We use the variable from LWS Database: anw (adjusted disposable net worth) for all countries apart from Denmark, Australia and Norway. For Australia and Denmark we use inw (integrated net worth). For Norway we take dnw (disposable net worth). For majority of countries: Austria, Canada, Finland, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, Spain, the UK, the US, net worth includes life insurance and voluntary individual pensions. For Denmark and Australia net worth includes pension assets and other long-term savings.

7 LIS PPP deflators, http://www.lisdatacenter.org (July 26, 2024). Luxembourg: LIS.

8 We use the definition from the LWS database: low (less than upper secondary education completed (never attended, no completed education or education completed at the ISCED 2011 levels 0, 1 or 2), medium (upper secondary education completed or post-secondary non-tertiary education, completed ISCED 2011 levels 3 or 4), high (tertiary education completed, completed ISCED 2011 levels 5 to 8)

References

| Emmons, W. R., Kent, A. H., & Ricketts, L. (2019). Is college still worth it? The new calculus of falling returns. The New Calculus of Falling Returns, 297-329. |

| Maldonado, L. C., & Nieuwenhuis, R. (2015). Family policies and single parent poverty in 18 OECD countries, 1978–2008. Community, Work & Family, 18(4), 395-415. |

| Morelli, S., Nolan, B., Palomino, J. C., & Van Kerm, P. (2022). The Wealth (Disadvantage) of Single-Parent Households. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 702(1), 188-204. |

| Nieuwenhuis, R., & Maldonado, L. (2018). The triple bind of single-parent families: Resources, employment and policies to improve well-being. Policy Press. |

| OECD (2019), Education at a Glance 2019: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/f8d7880d-en. |

| Scott III, R. H., Mitchell, K., & Patten, J. (2022). Intergroup disparity among student loan borrowers. Review of Evolutionary Political Economy, 3(3), 515-538. |

| Scott III, R. H., Patten, J. N., & Mitchell, K. (2023). Bait and Switch: How Student Loan Debt Stifles Social Mobility. Springer Nature. |

| Sierminska, E. (2018). The ‘wealth-being’ of single parents. The triple bind of single-parent families, 51. |

| Sierminska, E., Smeeding, T., & Allegrezza, S. (2013). The distribution of assets and debt. Income inequality: Economic disparities and the middle class in affluent countries, 285-311. |

| Wolla, S. A., & Sullivan, J. (2017). Education, income, and wealth. Page One Economics®. |