Issue, No.3 (September 2017)

Global inequality in a more educated world

The debate on whether globalization has or not increased inequality has been going on for a while, but the recent wave of populism – with its anti-trade, anti-immigration and nationalistic stances – has made it, again, quite relevant. Globalization has affected the distribution of incomes, but erecting barriers to trade may not help those (countries or groups of people within countries) who are on the losing side, and may likely be worse for all. When looked at with a long run and global perspective, globalization record is not so bad. This short piece tries to offer this perspective. In addition, it shows what is likely to happen to global inequality as more educated young cohorts, especially from developing countries, will enter the global labor market. It concludes that rather than curbing the trends, it would be more useful to manage the process of globalization and its consequences. At a time when more multilateral cooperation and innovation in social protection are needed, less seem to be on offer.

Globalization and within-country inequality

Globalization is usually described in terms of the international integration of national markets through goods and capital flows. Other aspects are often cited, such as international diffusion of ideas, culture, technology, and the movement of people. The trends of these variables have been described in a vast literature, and there is a consensus that globalization has greatly advanced in the last three decades or so.

Richard Freeman (2008) proposes a compelling way of characterizing the recent wave of globalization. He contends that a truly global labor market took shape almost all at once in the 1990s, when China, India, and the former Soviet bloc joined the global economy, doubling the size of the labor pool from 1.46 billion workers to 2.93 billion workers. With increasing international trade, factor markets get more integrated, and that is why Freeman’s way of describing globalization is quite illuminating, especially if one is interested in the link between globalization and inequality. Since the new entrants were mainly low skilled and low wage workers, increasing trade with China, India, and the ex-Soviet bloc meant that unskilled workers in high income countries (as well as in developing countries which were already integrated in the global trade system) were under pressure. The standard prediction from trade theory was that inequality (at least in terms of the skill premium) would increase in high income countries and that it would decrease in developing countries.

However, many empirical studies have not confirmed this prediction (for a thorough review, see Goldberg and Pavcnik, 2007) highlighting that inequality has been increasing instead within many developing countries during this period of expanding globalization. Indeed, several other factors were contributing to distributional changes. Economists have been arguing about the relative importance of trade versus technological change, when debating on the causes of the increasing skill premium. While trade may have reduced the skill premium in developing countries, skill-biased technological change may have increased it. But even this rationalization has some problems, as trade itself often induced innovation or maybe just faster adoption of new technologies. In addition, starting around the

mid-1990s, growth accelerated across most of the developing world causing further distributional changes (and complicating the identification of the specific impact of trade on inequality). In sum, one can see an evolution of the literature with earlier papers attributing a larger weight to technology and more recent papers emphasizing the importance of trade. As for the high-income countries, in a VoxEU post, Krugman (2007) points out that “it is no longer safe to say that the impact of trade on inequality is minor”.

Others had expressed concerns over the distributional consequences of globalization. About 20 years ago, Rodrik (1997) wrote “Has globalization gone too far?” a book focused on these issues, and described a possible backlash against globalization. A 2007 World Bank report titled “The next wave of globalization” again warned about hostile responses to international trade and migration flows. More recently, researchers have established a clear link between the polarization of the voting and exposure to trade (see Autor et al., 2016, for the US, and Colantone and Stanig, 2017, for the European countries).

Globalization and between-country inequality

Another relevant question is what happened to inequality between countries. Has the world overall become more equal, even if inequality within some countries has increased? To answer this question, one needs to compare incomes (or consumption) for individuals across all countries in the world and for at least two points in time. In other words, ideally one needs a global household survey. This is not yet available, but thanks to the increasing availability of high quality national household surveys and the harmonization work of institutions like the Luxemburg Income Study (LIS), the World Bank and others, it has been possible to construct a global income distribution for several points in time and appraise the evolution of global inequality. A recent well-known assessment of global inequality has been offered by Lakner and Milanovic (2015) who report a drop of the global Gini index from 72.2 in 1988 to 70.5 in 2008. This decline in global inequality can be largely explained by a reduction of inequality between countries due, in turn, by the economic progress in low- and middle-income countries, particularly by the sustained growth of populous countries like China and India. Lakner and Milanovic neatly summarize the evolution of the global income distribution with a growth incidence curve that displays the growth rate experienced since the fall of the Berlin Wall by each percentile of the global population.

This growth incidence curve has a profile of an elephant. It shows clearly that the highest growth rates have been experienced by the middle global percentiles, which correspond broadly to the middle class in China, and that the lowest growth rates have been recorded for the bottom 10 percent (the tail of the elephant) and for those with incomes between the 80th and 95th percentiles (the base of the trunk). This latter group comprises, amongst others, the lower middle class of the US. Another stylized fact highlighted by this graph is that the top percentiles (the tip of the trunk of the elephant) have also enjoyed very high growth rates. This graph thus shows both the catching up of poor countries such as China and India, and the stretching of the distributions within countries.

From this and other studies one concludes that global inequality has come down and that most of the reduction is explained by a reduction of inequality between countries. Is this a relevant result? Or asked differently, is global inequality a useful concept? Some, for example Bhagwati (cited in Milanovic) taking quite a strong position, say that a global Gini is ‘a lunacy’, an irrelevant number. In fact, the argument goes, there is no global government that can deal with global inequality. Social contracts, implicit in the formation of national states, are established at country levels, and a global Gini is just a number with no addressees.

But if one were to evaluate the world impact of the liberalization of trade, the diffusion of technology and globalization in general, then the global population is the relevant one. Equity (national or international) is valued by people. There is abundant evidence that relative, and not only absolute, levels of incomes matter for welfare. Even if there is no global government, globalization increases awareness of others’ incomes, and the management of the possible tensions requires multilateral agreements.

The recent surge of populism (Rodrik, 2017) makes the achievement of new encompassing multilateral agreements quite unlikely, thus asking what would be the most likely evolution of global inequality in the future a quite relevant and interesting question.

A look at the future of global inequality

In a recent paper, Ahmed et al. (2017) investigate this exact question. In this study, we make two main contributions: firstly, we identify a forthcoming education wave that is altering the skill composition of the global labor supply, and impacting income distribution, at the national and global levels; and secondly, by using a general-equilibrium macro-micro simulation framework that covers harmonized household surveys representing almost 90 percent of the world population, we offer an estimation of the distributional impact of this education wave.

On current trends, based on UN population projections (UN, 2015) and current rates of educational enrollment (conservatively kept constant into the future), the world will see the number of skilled workers rising from 1.66 billion in 2011 to 2.22 billion by 2050, an increase of about 560 million or 33 percent. Note that this prediction is based on what is already in the pipeline: young better educated cohorts entering the workforce while older less educated ones are exiting. With increases in educational efforts, the education wave may actually be even stronger. As in the case of the great doubling of the 1990s, the role of developing countries is crucial. Due to their investments in education and their growing populations, developing countries will contribute all of the additional workers to the world pool of educated workers. The number of skilled workers in high-income countries is projected to decline, from 603 million in 2011 to 601 million in 2030 and 594 million in 2050.

Not exactly another great doubling, but still a dramatic change. In 2011, each skilled worker in high-income countries was sharing the global market with two skilled workers in developing countries;, while by 2030, this ratio will be one to three. The increase in the supply of skilled workers will likely drive down the education premia these workers enjoy (other things being equal), and it may affect inequality within countries in a beneficial way. This kind of result has, for example, already been observed in developing countries in Latin America and the Caribbean (Lopez-Calva and Lustig, 2010). Note that,

because of trade links, wages of skilled workers in high-income countries will also come under pressure even if their domestic supply will not be increasing.

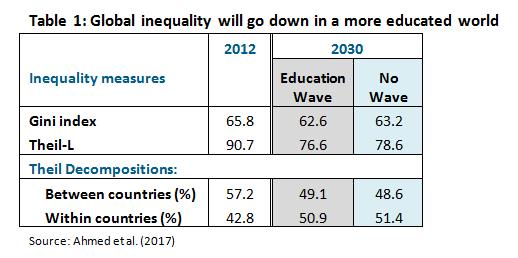

In terms of global inequality the results are summarized in this table:

These results confirm that the world will become more equal by 2030 as it becomes more educated. The (individual-based) Gini index falls from 65.8 in 2012 to 62.6 in 2030, while the Theil-L index is reduced from 90.7 to 76.6. Compared to recent patterns, these results suggest a continuation of the reduction in global inequality. During the great doubling of the global labor force, global inequality decreased by 2.3 percentage points in a 20-year interval from 1988 to 2008 (Lakner and Milanovic, 2015). Our education wave scenario shows a comparable reduction of 3.2 percentage points. As in the previous period, global inequality decreases mainly because, on average, poorer countries are catching up. At the beginning of the period, the contribution of the ‘between-countries’ component to total inequality is close to 60 percent. However, by the end of the period, the between-country component drops to less than 50 percent while the within-countries component correspondingly rises to slightly above 50 percent. This means that, in the future, developments of inequality within countries will become more important in the evolution of global inequality. The world will start becoming more unequal, if inequality within countries will keep rising.

The importance of the education wave in the dynamics of inequality within countries can be seen by comparing the results of the education wave with those of the no-wave scenario (a scenario where the numbers of both skilled and unskilled workers grow at a same rate) in the last column of the above table. The decreases of the skill premium in the education wave scenario pushes down inequality within countries, while this is not the case in the no-wave scenario. As a result, the within-group component in the no-wave scenario, as well as total inequality, are higher than those in the education wave.

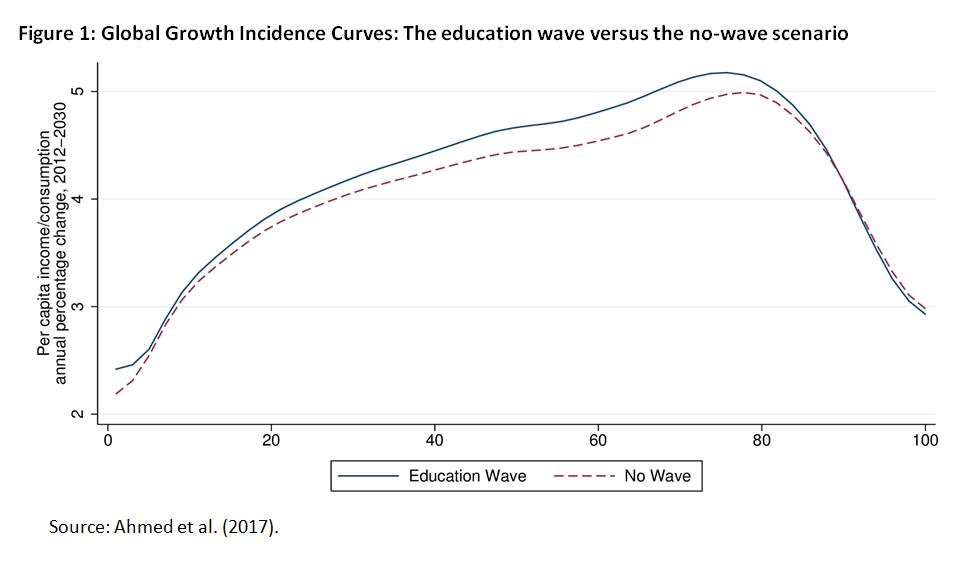

Comparing the global growth incidence curves (GICs) for the education wave and the no-wave scenarios is another way of illustrating the change in the global distribution.

These GICs highlight several interesting points. First, the education wave provides its highest benefits for the population with incomes between the bottom 20 and top 20; growth rates for the groups at the two extremes of the distribution are 1 to 2 percentage points lower than for the group in the middle. Second, the no-education wave rates of income expansion are below those of the education wave scenario for everyone with incomes up to about the 90th percentile. This is expected as the education wave is mainly a wave in the developing world. Third, the distance between the two lines appears small but, for the middle of the distribution and the bottom 5 percent, the difference should not be underestimated. In fact, half a percentage point gap in growth rates accumulates to 10 percent larger incomes after 20 years, a non-trivial difference.

A more educated world – more equality?

This 2030 scenario analysis is a big thought experiment, but still provides useful information. It shows that the number of high incomes to developing countries’ skilled workers will reach, at least, the 1-to-3 proportion by 2030, up from the current 1-to-2. It also answers the question of what would happen to global inequality once the world will become more educated. As shown by the ‘new’ elephant graph above, there will be gains but they are not uniform, and there will be distributional tensions.

Education, as it has been in the past, can still play the role of equalizer, but there is an important caveat. The global inequality reduction described in this thought experiment, depends on no changes in policies. New trade barriers, as other nationalistic policies, while justified as a remedy to the unfair consequences of globalization, may backfire, and global and local inequality may increase. The gains from international trade are inexorably linked

with its impact on shifting resources – on destroying as well as creating jobs. Curbing trade may mute distributional tensions but also erase overall gains. Policymakers should focus on managing the adjustment. But this is often more complicated than increasing tariffs, as it means opening a discussion on how a society shares the burden, and the gains, of globalization.

References

| Ahmed, S. A., Bussolo, M., Cruz, M., Go, D. S., & Osorio-Rodarte, I. (2017), Global Inequality in a More Educated World, Policy Research Working Paper No. 8135. |

| Autor, D., Dorn, D., Hanson, G., & Majlesi, K. (2016), Importing Political Polarization? The Electoral Consequences of Rising Trade Exposure, NBER No. 22637. |

| Colantone, I., & Stanig, P. (2017), The Trade Origins of Economic Nationalism: Import Competition and Voting Behavior in Western Europe, BAFFI CAREFIN Centre Research Paper, 2017–49. |

| Freeman, R. B. (2008), The new global labor market, Focus, 26(1), 1–6. |

| Goldberg, P. K., & Pavcnik, N. (2007), Distributional effects of globalization in developing countries, Journal of Economic Literature, XLV(March), 39–82. |

| Lakner, C., & Milanovic, B. (2015), Global Income Distribution: From the Fall of the Berlin Wall to the Great Recession, The World Bank Economic Review, 30(2), 203–232. |

| López-Calva, L., and Lustig, N. (Eds.). (2010). Declining Inequality in Latin America: A Decade of Progress? Brookings Institution Press. |

| Rodrik, D. (2017), Populism and the Economics of Globalization, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 12119. |