Issue, No.1 (March 2017)

Occupational welfare in Europe: why we need to study it more than in the past in order to understand social inequalities

What is occupational welfare and why it is important while studying social outcomes?

Around sixty years ago Richard Titmuss invited to take a broader view on complex mechanisms of welfare provision (Titmuss 1958). He developed the idea that, alongside ‘social’ welfare (social benefits and services provided by the State), ‘fiscal’ welfare (tax incentives for individuals and firms to help them provide welfare) and ‘occupational’ welfare (benefits and services provided by social partners) are important sources of protection. While some seminal works focused on occupational welfare (OW) in the 1970s and the 1980s, such type of welfare provision has been in recent years a relatively neglected area in welfare state studies.

OW is in fact a very delicate but increasingly important area of research. In the following we list the main reasons why we need to study OW, and why it is so difficult to do so, especially in a comparative perspective. There are at least three good reasons for an analysis of OW in greater depth. First, from an empirical point of view, the level of spending and the number of workers covered by these programmes show its key and, in many countries, growing role. Secondly, OW is important for understanding recent trends in industrial relations, with welfare provision and workers’ social rights being one of the central issues tackled by social partners. Last but not least, OW is relevant for the ongoing transformations in the welfare state and its impact on social inequalities. Some of the more recent trends in the welfare state – benefit cutbacks, programme revisions, decentralisation, etc. – cannot be assessed in isolation from what happens to OW. Furthermore, OW plays an important role in terms of redistribution and inequalities. OW programmes may lead under certain circumstances to increased dualisation and widen socio-occupational inequalities among workers and their families.

Yet the study of OW entails some methodological problems. The first problem is related to the lack of a clear and universally accepted definition of OW. In particular, the concept is ambiguous if seen in the context of the contemporary welfare literature. Some scholars conceptualise OW with reference to the coverage model of statutory schemes rather than to the nature of the providers. Both public (social welfare in Titmuss) and supplementary schemes are thus occupational when they are based on employment. Secondly, we still lack a classification of OW in Europe. Thirdly, data collection has proved extremely difficult, especially in comparative terms. Important questions have to be addressed, especially for survey data.

Some recent progress on the analysis of OW and its impact on inequalities

The EU funded research project – Unemployment and Pensions Protection in Europe: The changing role of the Social Partners, PROWELFARE – has aimed at providing in-depth evidence of occupational schemes in the field of pensions and unemployment programmes in nine EU countries while addressing the problems mentioned above.

In the project we have defined OW as the sum of benefits and services provided by social partners – employers and trade unions (by themselves or with the participation of others) – to employees over and beyond state benefits, on the basis of an employment contract.

The project shows that the scope of occupational schemes varies across policy areas and between countries. As for the latter issue, we have distilled four different country clusters. The clusters are defined on the basis of two analytical dimensions: the diffusion of OW across the workforce; the homogeneity of the protection across social and occupational groups (Natali et al. 2017).

The first cluster, Sweden and the Netherlands in our project, is characterised by an ‘encompassing’ OW: differences in coverage and level of protection among workers are low, while there is broad coverage of a variety of social risks for a large majority of workers (more than 70% of employees).

The second cluster, represented by the UK, Germany and Belgium, shows less widespread coverage (between 30 and 70% of the employees) and more evident differences in the protection provided by OW across social and occupational groups. These countries represent a ‘wide and segmented’ OW, based on voluntarism.

Southern Europe, Italy and Spain in our project, but also Austria, can be found in the third cluster, defined as a ‘limited and segmented’ OW system with generally low to medium levels of coverage (below 30% of employees covered by OW schemes). In this cluster, there are huge differences in terms of coverage and generosity of OW programmes across industries, sectors, companies and types of employment contract.

In Central-Eastern European countries, Poland in our project, OW barely exists and there have been no signs of an increase in recent years.

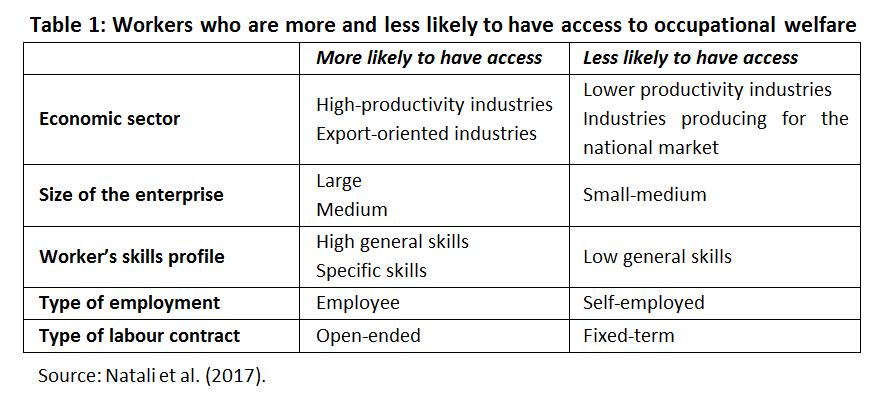

As for the impact of OW on inequalities, the project confirms that there is a risk that OW increases inequalities in the access to social protection. Table 1 summarises the main lines of segmentation created by OW: by industrial sector, size of company and occupational group. High-productivity industries (e.g. pharmaceutical, banking and finance, energy production), as well as those which are more export-oriented (automotive industries), offer more frequent and more generous occupational welfare schemes to their workers.

OW coverage is generally high in sectors predominantly requiring workers with high general skills and/or with specific skills, such as those of blue-collar workers in many manufacturing enterprises. Coverage is usually low in those enterprises requiring low general skills from the majority of their workers (e.g. tourism, personal services and retail). The size of the enterprise also matters: SMEs offer less frequent and less generous occupational welfare programmes than medium and large companies.

Practically everywhere workers with a fixed-term contract find it more difficult to access benefits than employees with an open-ended one. Moreover, migrants and, in many countries, women are less likely to be entitled to occupational welfare schemes. They are often employed in industries and enterprises more unlikely to provide occupational benefits, or because their labour contract and skills’ profile do not allow them to accede OW.

Looking at the different countries under scrutiny, the Scandinavian countries and, even more, the Netherlands seem to have developed an OW model in which the risks of welfare dualism are highly reduced (although not totally absent), especially when compared to Anglo-Saxon, Continental and Southern European countries. It seems clear that the only way to limit, if not avoid, inequalities created by OW schemes is to provide the conditions enabling coverage of the vast majority of the (working) population. Half-way situations create de facto welfare dualism.

What are the remaining obstacles for cross-national research?

Doing research on OW schemes, especially if the focus is on the relationship between inequalities and occupational welfare, is still not an easy task. Even in the field of pensions, where information is more systematically collected, there are important issues in data collection that need to be addressed. In particular the issue is a delicate one for population’s (workers and households) survey data. The latter tend to underestimate the OW phenomenon. The reason is that questions on OW schemes are very difficult to answer: many employees do not have information about their occupational welfare rights. The challenges are more complicated outside pensions, where quantitative comparable data are even more scarce. Analysts need to refer to information on the individual/household level, knowing that we will still get an imperfect estimation of the phenomenon, and on the company level where data are often incomplete.

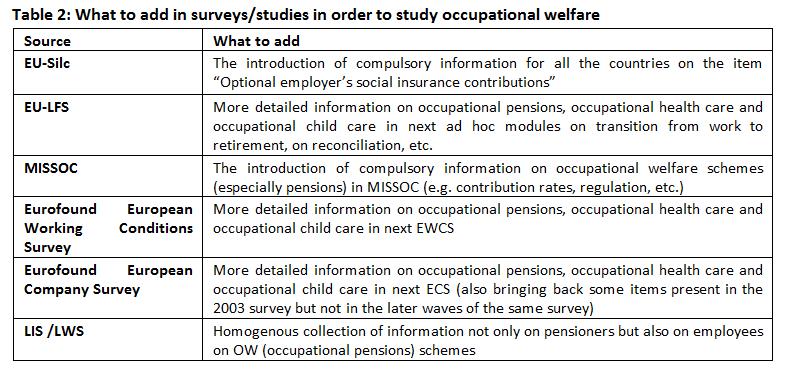

Nevertheless, with all these limitations and difficulties in data collection, there are potential ways forward. There are several sources of information on welfare issues at the EU level that could be used, even without creating new ad hoc surveys for data collection on occupational welfare schemes. It would be necessary to add specific questions/items inside these databases and surveys as illustrated more in detail in Table 2.

References

| Natali, D. ad Pavolini,E. with Vanhercke, B. (2017), Occupational Welfare in Europe. Risks, opportunities and social partner involvement in pensions and unemployment protection, ETUI, Brussels, forthcoming. |

| Titmuss, R.M. (1958), Essays on the welfare state, London, Allen and Unwin. |