Issue, No.31 (September 2024)

The Geography of Inequality in Egypt: Decomposition Analysis and Regional Trends over 1999-2017*

Introduction

The analysis of economic inequality in Egypt – and, more broadly, in Middle East and North Africa (MENA) countries – has recently sparked an interesting debate regarding its extent and trends, generating quite a bit of controversy (e.g., Verme et al. 2014, Ianchovichina et al. 2015). Rising inequality has been cited as one of the factors behind the uprisings in Arab countries by media and academics. However, in Egypt, estimates of inequality measures at the national level, based on household surveys, suggest that inequality has been moderate and relatively stable over time (Al-Shawarby, 2014).

One way to reconcile this apparent paradox, not unique to Egypt and often referred to as the “Arab inequality puzzle”, is on technical grounds. Measuring economic inequality is often challenging, especially in developing countries where detailed and comprehensive administrative data on income and wealth are typically scarce or entirely unavailable. This may lead to substantial discrepancies between the way income inequality is measured and its true extent. In the case of Egypt, existing statistics may underestimate its true extent. One argument is that income inequality estimates are drawn from household surveys with various limitations, especially with respect to the “true” top incomes (Achcar, 2020). Hlasny and Verme (2018) addressed this issue. After correcting for problems such as the number of non-respondents in household surveys, the estimated inequality was found to be higher by a minimum of 1.1 to a maximum of 4.1 percentage points. Similarly, Van der Weide et al. (2018) argued that top income shares in Egypt were significantly underestimated. Using house prices to re-estimate the top tail of the income distribution, the revised Gini index was found to be 25% higher than the value reported in the World Bank’s statistics.1

Here, we revisit inequality in Egypt by looking at its geographical variation. This note, in particular, focuses on the sub-national dimension of inequality, including the urban-rural gap, and how income distribution has evolved within Egyptian regions (governorates) over nearly two decades. This is important because fairly unequal regions may coexist alongside relatively equal ones and individuals’ experience of inequality at the “local level” may reflect that.

The spatial dimension of inequality

Using ERF-LIS data based on CAPMAS surveys, we first decompose income inequality by population subgroups using the geographical location and calculate inequality within each subsample and between the means of the subsamples, to assess the importance of subgroups. In our case, the between-group and the within-group components measure the inequality contribution coming, respectively, from: (a) the differences in urban and rural means and the income differences inside each area; and from (b) the differences in governorates means and the income differences inside each governorate. For all measures, we detect extreme values via the interquartile range following the recent LIS procedure (Neugschwender 2020).

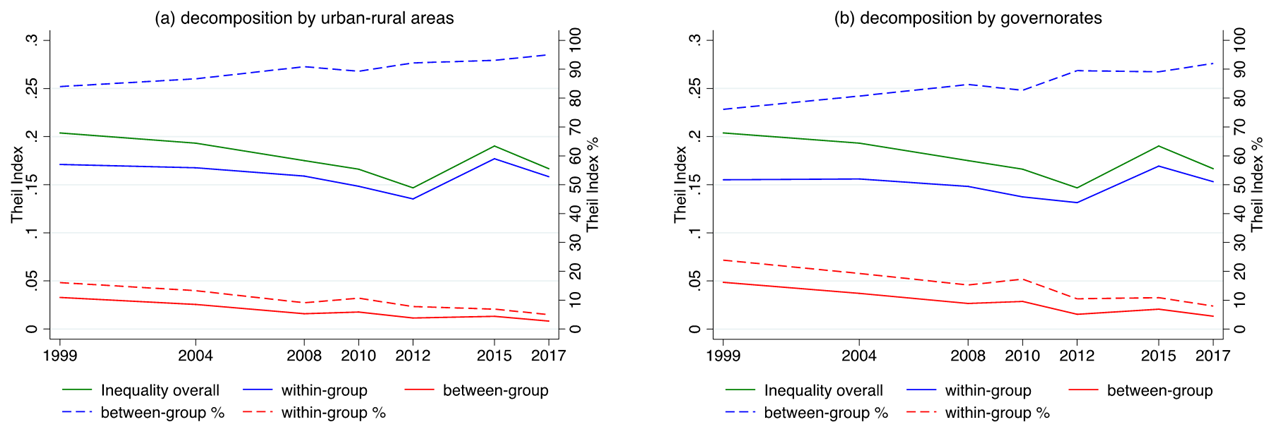

Figure 1 illustrates the Theil Index and subgroup decomposition over 1999-2017. Consistent with previous evidence, the overall level of inequality declined steadily until 2012, followed by an upward trend.2 At first glance, exploring the geographical divide, it is apparent that the within-component almost entirely explains overall inequality in Egypt, with the between component decreasing steadily over time. In 2017, the contribution of the within and between component in urban and rural areas is respectively 95% and 5%. Looking at the regional data, intra-regional inequality accounted for about 92% of the total in 2017, whereas inter-regional inequality significantly decreased over time and accounted for the remaining 8%. This indicates that overall inequality in Egypt is driven by specific regional dynamics.

Figure 1 – Income inequality in Egypt: Theil index and subgroup decomposition 1999-2017

Notes: Theil index decomposition of the equivalised disposable household income based on ERF-LIS data. Data are top-bottom coded detecting extreme values via the interquartile range.

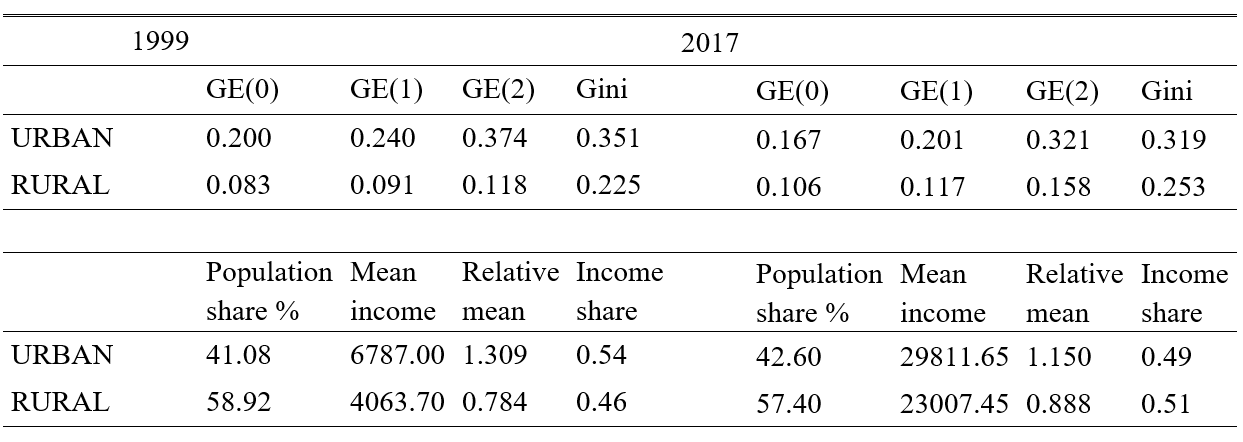

Table 1 reports further statistics for urban and rural areas illustrating the extent to which income disparities in each contributed to overall Egyptian inequality in 1999 and 2017. In line with the results of Milanovic (2014), Theil indices and Gini show that the influence predominantly stems from urban areas, reinforcing that the inequality gap remains largely geographical. It is between the four main Egyptian cities, and the rest of the country. In 1999, the mean income of the urban area was about 1.30 times the overall mean income, with the average per capita urban income being 67% higher than the average rural income. After nearly two decades it reduced to 29.5%.

Overall, although the initial gap was quite deep it significantly reduced over time. The income shares for urban and rural areas in Egypt have shifted significantly between 1999 and 2017. In 1999, urban areas received 54% of the income, while rural areas received 45%. By 2017, these shares had nearly reversed, receiving 49% and 51% respectively. This shift in income distribution occurs despite the population share remaining relatively stable between the two periods. This change suggests a significant realignment in income allocation, indicating that while income disparities between urban and rural areas have lessened, the distribution of income has become more balanced over time.

Table 1 – Subgroup indices and statistics in urban and rural areas

Notes: inequality measures calculated on equivalised disposable household income. GE(0) is the mean logarithmic deviation (MLD), GE(1) is the Theil index, and GE(2) is half the square of the coefficient of variation.

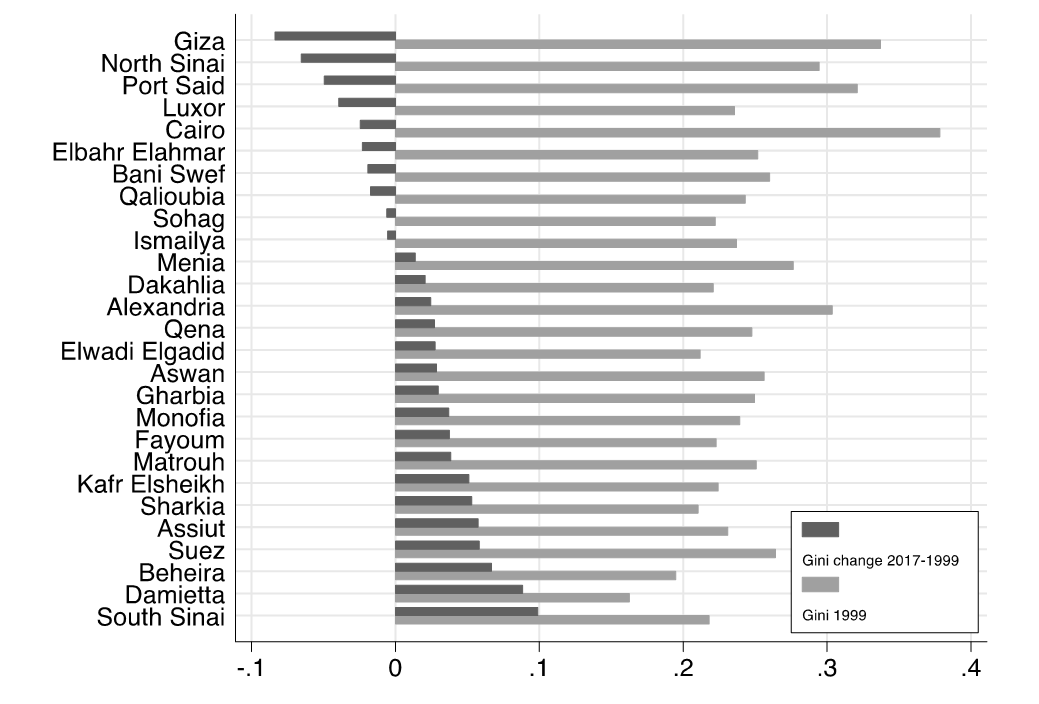

In more detail, how has inequality evolved within regions? Figure 2 plots the initial value of Gini in 1999 for each region and the corresponding change from 1999 to 2017. This indicates i) significant variation in income inequality levels across regions and ii) a notable increase in most regions. Interestingly, a closer look at the regional dynamics reveals that the most influential and unequal governorates are also those that have seen significant reductions, except for the case of Alexandria. Similarly, the surge of income inequality in the more egalitarian regions of Damietta, Beheira, and South Sinai is noticeable, with increases of approximately 9%, 7% and 10% points, respectively.

Figure 2 – Initial level of inequality and change over time: Gini, 1999-2017

Notes: Gini index calculated on equivalised disposable household income. Data for Elbahr Elahmar, Elwadi Elgadid, Matrouh, North Sinai and South Sinai are not available for 2017 and refer to 2015.

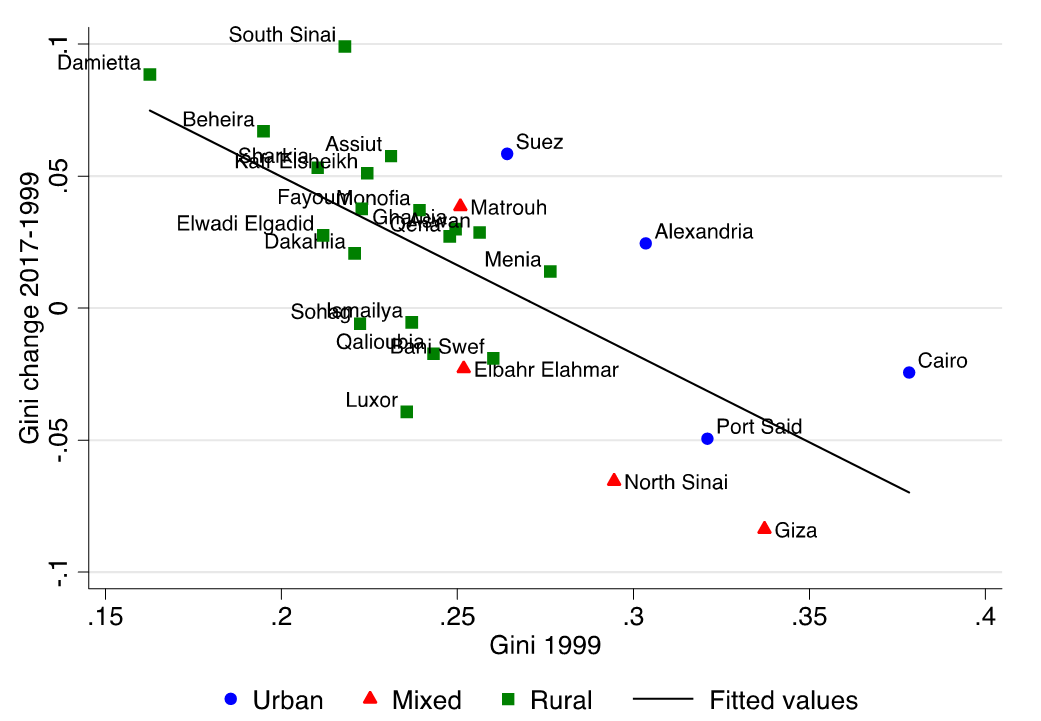

Figure 3 provides a visual indication of the relationship between the initial level of inequality and the 2017-1999 change. The negative linear relationship in the scatter plot shows that regions with higher initial levels of inequality seem to catch up with those having lower initial levels of inequality, thereby indicating that there may have been convergence during the 1999-2017 period.

Figure 3 – Initial level of Gini versus Gini change 1999-2017

Notes: Gini index calculated on equivalised disposable household income. Data for Elbahr Elahmar, Elwadi Elgadid, Matrouh, North Sinai and South Sinai are not available for 2017 and refer to 2015.

To test this empirically, we examine whether regions with lower inequality levels tend to experience larger changes in inequality, thereby catching up with regions with higher inequality levels. Regression estimates indicates that differences in within-region inequality expressed by the Gini index have reduced since 1999, on average. Specifically, according to the estimates, regions are converging to an average Gini index of 0.27. This test is also repeated for quintile shares of income and the poverty rate measured as the proportion of people living below 50% of median income. Results strongly support the hypothesis of convergence in all parts of income distribution and poverty, with the coefficients for the initial values being negative and statistically significant.

Concluding remarks

Analysing the spatial dimension of income inequality in Egypt over nearly two decades reveals a significant geographical gap largely attributed to urban areas, considerable variation in how income is distributed within regions, and a notable increase in inequality in most regions. However, the evidence also indicates that the gap between urban and rural areas is narrowing, and that differences in within-region income inequality have, on average, reduced since 1999.

The Egyptian case suggests that measuring and monitoring income inequality at the sub-national level matters. If we had only considered the national level, we would have concluded that inequality was moderate and stable. However, the sub-national data reveals that Egyptians experience varying levels of equality depending on their Governorate, with some regions being relatively equal and others more unequal. This is important to assess, for instance, if SDGs progress in reducing inequalities is geographically diffused.

How income is distributed at regional level is also important because a significant part of individuals’ experiences of economic inequality often occur at the local level. This affects political and social attitudes and behaviours and, in turn, individuals’ well-being (Peters and Jetten, 2023). From this perspective, the lens of regional-level inequality may help explain the “Arab inequality puzzle” — the apparent disconnect between the low and stable national-level inequality reported in the Arab societies and the popular perception of high inequality leading to the Arab Spring uprisings. The increasing regional inequality observed in both relatively equal and unequal regions in Egypt might be at the root of such perception. This aligns with the hypothesis that inequality may have fuelled, among other things, the political uprisings of the Arab Spring.

* This article is an outcome of a research visit carried out in the context of the (LIS)2ER initiative which received funding from the Luxembourg Ministry of Higher Education and Research.

1 Another effort to explain the apparent disconnect between inequality and social uprisings points to the deterioration of subjective well-being measures (Devarajan and Ianchovichina 2018).

2 The Gini index for Egypt was 0.314 in 1999, 0.293 in the year of the political uprisings in 2010, and 0.291 in 2017.

3 The corresponding test of unconditional beta-convergence is a regression of the observed absolute changes over time on a given inequality measure on the measure’s initial values across regions. For further details and results related to Egypt, refer to Savoia et al. (2024).

References

| Al-Shawarby, S. (2014). The Measurement of Inequality in the Arab Republic of Egypt: A Historical Survey, in P. Verme et al., eds., Inside inequality in the Arab Republic of Egypt: Facts and perceptions across people, time, and space. World Bank Studies. Washington, DC: World Bank. |

| Achcar, G. (2020). On the ‘Arab inequality puzzle’: The case of Egypt. Development and Change, 51(3), 746–770. |

| Devarajan, S., & Ianchovichina, E. (2018). A broken social contract, not high inequality, led to the Arab Spring. Review of Income and Wealth, 64, S5-S25. |

| Hlasny, V., & Verme, P. (2018). Top incomes and the measurement of inequality in Egypt. The World Bank Economic Review, 32(2), 428-455. |

| Ianchovichina, E., Mottaghi, L., & Devarajan, S. (2015). Inequality, Uprisings, and Conflict in the Arab World. Middle East and North Africa Economic Monitor. World Bank, Washington, DC. |

| Milanovic, B., (2014). Spatial inequality, in P. Verme et al., eds., Inside inequality in the Arab Republic of Egypt: Facts and perceptions across people, time, and space. World Bank Studies. Washington, DC: World Bank. |

| Neugschwender (2020). Top and bottom coding at LIS. LIS Technical Working Paper Series, No. 9. |

| Peters, K., & Jetten, J. (2023). How living in economically unequal societies shapes our minds and our social lives. British Journal of Psychology, 114(2), 515-531. |

| Savoia, F., Bournakis, I., Said, M., & Savoia, A. (2024). Regional income inequality in Egypt: Evolution and implications for Sustainable Development Goal 10. Oxford Development Studies, 52(1), 17-33. |

| Van der Weide, R., Lakner, C., & Ianchovichina, E. (2018). Is inequality underestimated in Egypt? Evidence from house prices. Review of Income and Wealth, 64, S55-S79. |

| Verme, P., Milanovic, B., Al-Shawarby, S., El Tawila, S., Gadallah, M., & El-Majeed, E. A. A. (2014). Inside inequality in the Arab Republic of Egypt: Facts and perceptions across people, time, and space. World Bank Studies. Washington, DC: World Bank. |